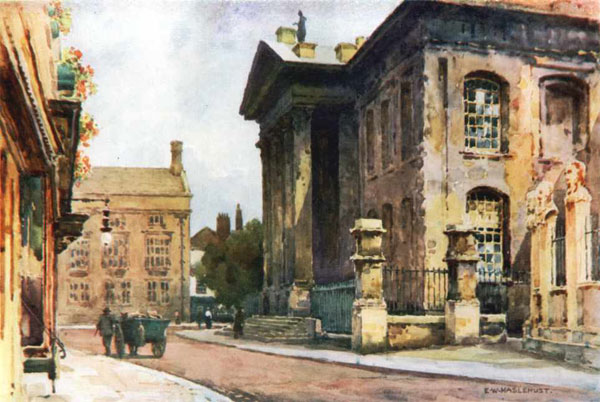

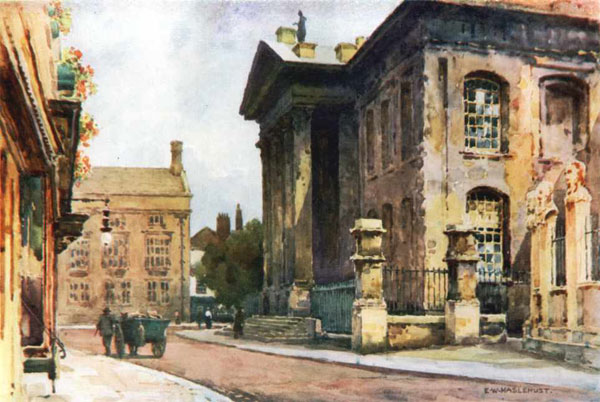

Oxford University was a large mass-producer of books by the 1820s. Despite this, it was still occupying a very elegant but modest-sized neo-classical building in the centre of Oxford designed for it in 1713 by Nicholas Hawksmoor. By the mid-1820s this building was bursting at the seams. This was made clear by an inventory of the Clarendon Bible Press undertaken by Richard Watts in January 1824. Watts had worked his way down the packed building starting at the three attics which together housed 4,067 feet of poling with bearers on which the dampened and printed sheets could be hung up to dry. Below these were a warehouse in the south east corner which contained a large hydraulic paper press and 165 paper stages ‘of various dimensions’; there was a Waste Room warehouse in the north east corner ‘for remainders’; a packing room with ‘a stout book press’ and another 650 feet of poling; a warehouse in the south west with a small hydraulic press and a forcing pump; and a warehouse in the north west of the building. Below these were the Upper Press Room (No. 1) to the north with 928 feet of poling and an eight-day clock; and Upper Press Room (No. 2) to the south east with 1,188 feet of poling. On the same level there appears to have been a ‘Reading Room’ (for reading proofs) with reading desks and leather chairs and scales ‘for weighing single sheets of paper’. Below these were the Lower Press Room (No. 3) in the north with 1088 feet of poling and bearers, lead sinks and racks for type. Even the stair wells were used, for on them were double case racks of various sizes which held a large number of pairs of types cases.

The Lower Press Room (No. 4) in the south east had 1,440 feet of poling and bearers. Between them the four press rooms seem to have accommodated seven large presses and eighteen smaller ones. Below these was a ‘white paper warehouse’ and a ‘Wetting Cellar’ with a large lead cistern, forcing pump and a large quantity of lead pipe plus over a ton of cast-iron and stone weights ‘for pressing the paper.’ Added to this were the newly arrived-technologies of ‘gas light fittings and apparatus generally’ and a ‘Hot air dispenser, as kept in complete order’.

What is striking about this inventory is that there is so much material and so many processes (and therefore, by implication, many people) packed into a small site. However, the feature that might most surprise the modern reader is the frequent listing of considerable lengths of poling, which would be used for drying. In total there were some 13,055 feet – or two and a half miles – of drying racks distributed over many rooms. This reminds us that at this time paper was damped before printing and thus had to be dried after it. This explains why there were so many troughs and sinks and weights (for holding paper down) listed in the inventory. Any increase in number of titles produced, or print runs ordered, would have had a considerable effect on the number of printed sheets that had to be dried on one or more of the rooms in the Clarendon Building. The results of the printers’ efforts would have been obvious to all who worked at the Press, for acres of damp print would have been fluttering, or hanging limply, over their heads. In winter it would have taken longer, in summer a shorter, time to dry but, as soon as the dried sheets had been harvested, their place would have been taken by new sets of dank texts.

Simon Eliot is Professor of History of the Book at the Institute of English Studies. He is the general editor of The History of the Oxford University Press.

Bottom image from: http://www.headington.org.uk/oxon/broad/buildings/south/clarendon.htm