In the run up to – and right after – the broadcast of the much awaited third season of BBC’s Sherlock earlier in 2014, blogs, reviews, articles, and conferences were abuzz with all things Sherlockian, analysing each and every conceivable aspect of the show: from the religious turn in fan appreciations of Holmes and Watson’s relationship (Poore 2012) to links between Victoriana, Steampunk and doctor Watson’s black Haversack jacket (Artt 2014). Yet one thing seemed to go unnoticed, for all its fleshly, flamboyant spectacle: the political implications of season two’s sexualisation of Irene Adler, the only female character who ever outwitted the legendarily astute Sherlock Holmes in Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories.

Whereas Doyle’s Adler, first appearing in ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ published in The Strand in 1891, is the only woman who beat Holmes at his own game by outsmarting him, in Gattis & Moffat’s irreverent updating and re-mixing of Doyle’s stories she becomes a scantily clad dominatrix who literally beats him. Instead on her brains, the focus of ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ is somewhere else: on Adler’s sexy body and sexuality. And here, in the ‘sexsation’ (Kohlke 2008) of this neo-Victorian interpretation of Adler, one detects the adaptation’s neo-conservative and neo-colonialist rub. What, at the first glance, would – and easily could – be dismissed as a mere ‘sexing up’ of the Victorian text for contemporary sensation-seeking audiences turns out to be a pleasurable visual distraction from the politically regressive interventions of the adaptation.

Whereas Doyle’s Adler, first appearing in ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ published in The Strand in 1891, is the only woman who beat Holmes at his own game by outsmarting him, in Gattis & Moffat’s irreverent updating and re-mixing of Doyle’s stories she becomes a scantily clad dominatrix who literally beats him. Instead on her brains, the focus of ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ is somewhere else: on Adler’s sexy body and sexuality. And here, in the ‘sexsation’ (Kohlke 2008) of this neo-Victorian interpretation of Adler, one detects the adaptation’s neo-conservative and neo-colonialist rub. What, at the first glance, would – and easily could – be dismissed as a mere ‘sexing up’ of the Victorian text for contemporary sensation-seeking audiences turns out to be a pleasurable visual distraction from the politically regressive interventions of the adaptation.

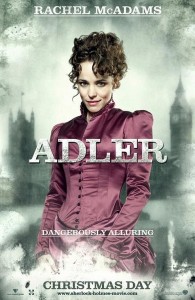

The erasure of Adler’s agency is paradoxically depicted through her representation as supposedly strong and in control because of her overt sexuality and the use of her body as a weapon. Such use of sexuality – as a means of ‘empowerment’ – belongs squarely to the postfeminist discourse in popular culture and media, especially prominent since the 1990s. In Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (2009) that preceded BBC’s Sherlock, Adler’s ‘empowerment’ is performed through her characterisation as an independent, ‘dangerously alluring’ vixen who has her own agenda– yet, ultimately, a heroine whose agency is re-inscribed within a patriarchal system of power-play. She does not act on her own, but as a pawn in Moriarty’s game, and her agency, greatly dependent on the use of her own sexuality, is eventually neutralised by the cold-blooded criminal mastermind in the film’s sequel (2011). Like Ritchie’s films, Moffat and Gatiss’s ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ (episode one of the second season, 2012) downplays Holmes’s restrained expression of admiration for Adler and eliminates her besting of Holmes, focusing instead on her feminine wiles. However, their ‘updating’ of Adler as a dominatrix and a sexual woman – a superficial rescue mission of the supposedly buttoned-up Victorian character – gives her only the temporary power of the female body as fetish: as soon as this power is over-reached, Adler is promptly humiliated and punished.

The erasure of Adler’s agency is paradoxically depicted through her representation as supposedly strong and in control because of her overt sexuality and the use of her body as a weapon. Such use of sexuality – as a means of ‘empowerment’ – belongs squarely to the postfeminist discourse in popular culture and media, especially prominent since the 1990s. In Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (2009) that preceded BBC’s Sherlock, Adler’s ‘empowerment’ is performed through her characterisation as an independent, ‘dangerously alluring’ vixen who has her own agenda– yet, ultimately, a heroine whose agency is re-inscribed within a patriarchal system of power-play. She does not act on her own, but as a pawn in Moriarty’s game, and her agency, greatly dependent on the use of her own sexuality, is eventually neutralised by the cold-blooded criminal mastermind in the film’s sequel (2011). Like Ritchie’s films, Moffat and Gatiss’s ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ (episode one of the second season, 2012) downplays Holmes’s restrained expression of admiration for Adler and eliminates her besting of Holmes, focusing instead on her feminine wiles. However, their ‘updating’ of Adler as a dominatrix and a sexual woman – a superficial rescue mission of the supposedly buttoned-up Victorian character – gives her only the temporary power of the female body as fetish: as soon as this power is over-reached, Adler is promptly humiliated and punished.

The degradation of Adler develops visually through the use of costumes on-screen. By the end of ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’, the dangerously sexual female nude of the former colonial centre is displaced into a Pakistani desert and transformed into a kneeling powerless bundle of indigo-blue wraps. In a stereotypically Victorian fashion (Boehmer 1995: 27-28), that paradoxically does not feature in Doyle’s text, this fallen woman has to be punished, banished to the former colonial space, and saved by the (show’s) hero, Sherlock. And not only that: Adler’s ‘empowered’ flesh is transformed into the most oppressed image of the female body in Western media: that of the hijab-wearing woman. At the same time, her final appearance confirms her loss of agency and reaffirms what Angela McRobbie described as the postfeminist gendered “boundaries between the West and the rest” (McRobbie 2009: 1), curiously introducing both the notion of the global terrorist threat and a belated Orientalist notion about the colonial space not even present in the Victorian story. In addition, the repeated reminders of Watson’s stint as an army doctor during the Afghanistan war function as oscillating echoes of Victorian imperialist ventures into the area, amplifying the reverberations between the imperialist past and the precarious present of the new, global, neo-colonialisms.

Antonija Primorac is an Assistant Professor in English Studies and the Head of English Department at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Split, Croatia. In the summer of 2013 she was a visiting fellow at IES doing research on neo-Victorianism and screen adaptations of Victorian heroines. The resulting article was published as “The Naked Truth: The Postfeminist Afterlives of Irene Adler” in the on-line, peer-reviewed Journal of Neo-Victorian Studies (2013) 6:2, pp. 89-113, hosted by Swansea University.

Images: 1. Laura Pulver as the defeated & orientalised Irene Adler in ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ (BBC’s Sherlock, 2012). 2. Rachel McAdams as the ‘dangerously alluring’ Irene Adler in Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (2009)

Very informative and excellent complex body part of content material, now that’s user genial (:.