Senate House Library often provides small displays to support conferences. The Library scans lists of forthcoming SAS conferences to offer displays, where timing fits and it has relevant holdings, and sometimes conference organisers approach the Library to request displays. When The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Solutions and Resolutions organisers requested a display on the back of one that had accompanied the Victorian Popular Fiction Association’s conference in July, the Library was delighted to comply, having already had the Drood conference in its sights.

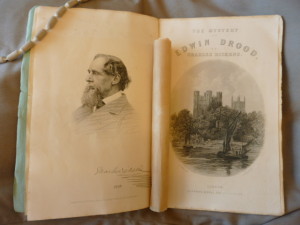

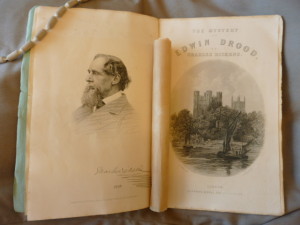

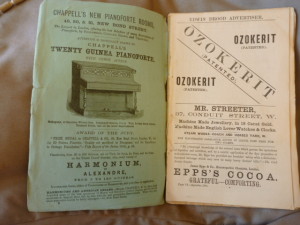

How does one select material in such instances? The original ‘parts’ were a clear must: Dickens parts are always popular. Those of Edwin Drood show the work of two illustrators / interpreters – Dickens’s son-in-law Charles Collins for the cover, and the younger Luke Fildes for the rest. The original parts are also the only way to demonstrate the enormous initial popularity of the publication, with the large number of advertisements: in the first part, 36 pages, headed ‘Edwin Drood Advertiser’ at the front, and another seven at the end, not to mention the covers. Seeing the parts means seeing for oneself how readers of 1870 also imbibed advertisements for Chappell’s twenty-guinea pianoforte, Mr Streeter’s machine-made jewellery, Epps’s cocoa, croquet sets, and the Scottish Widows’ Fund Life Assurance Society among other goods and services.

The rather drab, modest American first edition (Boston: Fields, Osgood, 1870) ultimately missed out on display for lack of space; and the completion ‘by the spirit-pen of Charles Dickens, through a medium’ (i.e. the Vermont printer Thomas Power James; Brattleboro: T.P. James, 1873), was omitted from the display because the book is unattractive. But we did want to capture the speculation that Dickens’s unfinished novel caused and the way it captured the imagination. To that end we had one of the many dramatic adaptations and completions of the novel, Eric Jones-Evans’s John Jasper’s Secret (1951) – a version which shows the international popularity of the theme through the fact that it was subsequently broadcast in New Zealand and Australia, although this fact does not emerge from the printed text – and a prose continuation by Walter E. Crisp (1914). The other items shown are seminal to Drood studies: John Forster’s biography of Dickens for its intimation of plot development, and John Cuming Walters’s edition of the novel, including a tabulation and discussion of solutions and sequels.

I regret not having had space for Andrew Lang and M.R. James’s brief About Edwin Drood, a resurrection of two journal publications from 1911 here produced by a modern private press, the Tragara Press in Edinburgh, in 1983. Yet the pretty floral cover which would have been shown under glass is insignificant compared with Lang’s Dialogue about The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which took place in Baker Street between Sheerot and his friend and narrator Whatson.

Dr Karen Attar is Rare Books Librarian at Senate House Library, University of London.