This post originally appeared on Philip Mould & Co, written by Professor Warwick Gould FRSL, FEA, FRSA.

Philip Mould & Co. are grateful to Professor Warwick Gould FRSL, FEA, FRSA, Emeritus Professor, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of English Studies, University of London, for his insight into Antonio Mancini’s Portrait of William Butler Yeats which is currently on display at our Masterpiece stand (A3).

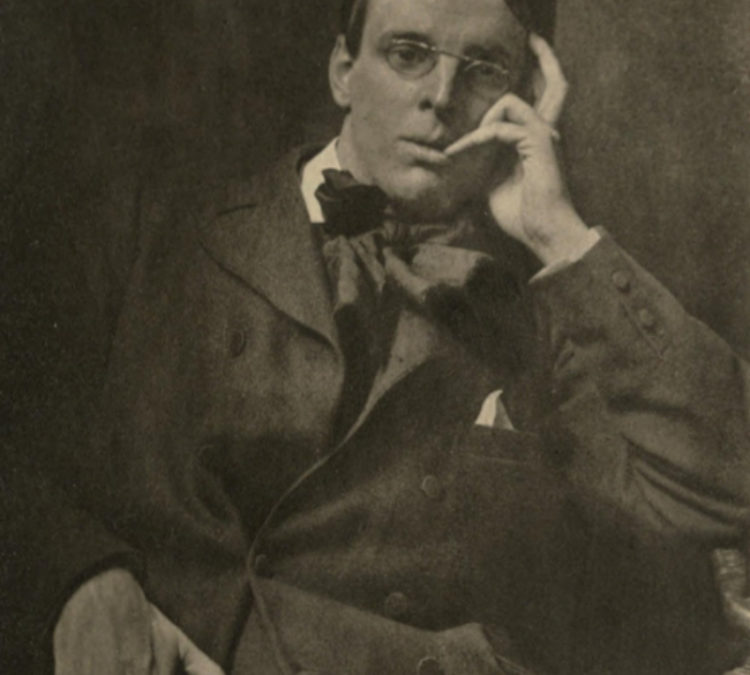

The astonishing likeness of the great Irish poet William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) was undertaken by Antonio Mancini (1852-1930) in Dublin in 1907 and ranks amongst the most successful formal portraits of a poet taken in the first half of the 20th century. It remained in the possession of the Yeats family until 2017. Yeats, who wrote about the sitting which took about one hour, is shown mid-career with his achievements well-established, and as if caught in conversation. By all accounts Yeats was delighted with the portrait and it was subsequently used as a frontispiece for two volumes of his Collected Works published in 1908. Mancini was known for his energetic approach to portraiture and Yeats described him as ‘the man who splashes on great masses of colour, so that his painting looks at times as if it were modelled in relief’.

‘Impudent, Immoral, and Reckless’: Antonio Mancini’s Portrait of Yeats

ANTONIO MANCINI (1852-1930) arrived in Dublin in the autumn of 1907, where doors were opened for him by his great admirer, the London art dealer, Sir Hugh Lane. He had met Lane in Rome in 1904, and painted him there in 1905 or 1906, but in Dublin, it was flattery which got him everywhere. As he sold himself to potential sitters, he stole the show, a one-man opera buffa. W. B. Yeats wrote to his patron, John Quinn on 4 October 1907:

“Mancini … the man who splashes on great masses of colour, so that his painting looks at times as if it were modelled in relief, is here in Dublin now. He has come to paint Lady Gregory for Hugh Lane’s new Gallery. He is a dear creature with no English. I met him last night. I am naturally delighted with him as he presented me with a large chrusantheum and a vehement gesture of his lifted hand, and standing on tip toes cried out in French, `The master is very tall—very beautiful.’”

Mancini’s portrait of Lady Gregory is indeed now in what had been the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, now the Dublin City Gallery (The Hugh Lane). According to Yeats’s ‘The Municipal Gallery Revisited’, J. M. Synge thought the Gregory portrait the ‘greatest since Rembrandt’. [1] It was one of a number of works commissioned by Lane for the founding collection: Mancini’s portrait of Lane himself, surrounded by various objets d’art, is another. The Gallery opened in Clonmell House, Harcourt Street, on 20 January 1908 with nearly three hundred works, Lane having donated about a third of these. His powerful philanthropic purpose was to bring international and Irish art to ordinary people.

Others in Mancini’s world were also well-known in Ireland. The French novelist Paul Bourget had been a guest of the Comte de Basterot at Duras, Co. Galway in 1896, where he had met Yeats and other members of the Lady Gregory circle. John Singer Sargent, who thought Mancini ‘the best living painter’, may also have opened doors for him, as he had when Mancini had come to London in 1901. [2]

‘CRISTO, O‘

It was Lane who invited Yeats to sit for Mancini’s pastel, which was done on 6 October 1907, probably in a large room in what was shortly to become the Municipal Gallery, where Mancini had painted Lady Gregory and Ruth Shine, Lane’s sister. Both Lady Gregory and Yeats record Mancini’s technique of setting up a frame criss-crossed with threads through which he would study his sitter. He would transfer what he saw through the frame onto a similar grid either very close to the painting surface or drawn upon it. [3] To Gregory he explained in ‘incomprehensible French, though sometimes turning to little less comprehensible Italian’ that this had been the method of ‘some great master’. [4]

“… he would go to the very end of the long room, look at me through my net, then begin a hurried walk which turned to a quick trot, his brush aimed at some feature, eye or eyebrow, the last steps would be a rush, then I needed courage to sit still. But the hand holding the brush always swerved at the last moment to the canvas, and there in its appropriate place, between its threads, the paint would be laid on and the retreat begin.”

The session with Yeats began slowly but seems to have caught fire when Yeats burst into spontaneous laughter.

The pastel, which I still have, was an evening’s work. Mancini put his usual grill of threads where the picture was to be and another grill of threads corresponding exactly with it in front of me. He did not know anything about me, we had no language in common, and he worked for an hour without interest or inspiration. Then I remembered a story of Lane’s. Mancini, Italian peasant as he was, believed that he would catch any illness or deformity of those whom he met. He was not thinking of microbes, but of some mysterious process like that of the Evil Eye. He had just been painting someone who had lost a leg, and whose cork leg he believed was having a numbing effect on his own. He worried Lane with his terror—‘My leg is losing all power of sensation,’ he would say at intervals. The thought of this story made me burst into laughter and Mancini began to draw with great excitement and rapidity. [5]

Elsewhere Yeats remembered that Mancini finished ‘in an hour or so working at the last with great vehemence and constant cries, “Cristo, O”, and so on’. [6]

SOMETHING BOROCO: IMPUDENT, IMMORAL, AND RECKLESS

At the time, the forty-two-year-old Yeatswas preparing a new Collected Works in Verse and Prose for the Shakespeare Head Press, a sumptuous, vellum-bound Library edition in eight volumes (1908). New versions of old texts demanded new images of the poet, as frontispieces to various of the volumes, and Mancini’s portrait was under consideration. Mancini’s work was on display in London, at the New Gallery, 121 Regent St, in early December 1907.

“I went yesterday to the new gallery & heard [William] Rothenstein praise the Manchini [sic] picture of Lane—a man who was with him disliked it but Rothenstein said ‘If I were wearing seven hats I would take them all off before it’. He then said ‘it is horrible, it is like a bad Italian building something Boroco but all the same it is magnificent inimitable—It kills everything else.’” [7]

Yeats had similarly mixed, intense reactions to Mancini’s pastel. Moreover, earlier that summer, Augustus John had been at Coole Park, Co. Galway with Yeats and others of the Lady Gregory circle and Yeats had several times submitted as ‘rather a martyr’ to John who had etched the results: ‘a great etcher with a savage imagination’. [8] John’s and Mancini’s portraits challenged Yeats’s self-conception, becoming rival candidates for inclusion in his new collected edition.

“… Mancini who has filled me with joy, has turned me into a sort of Italian bandit, or half bandit — half cafe king, certainly a joyous Latin, impudent, immoral, and reckless. Augustus John who has made a very fine thing of me has made me sheer tinker, drunken, unpleasant and disreputable, but full of wisdom, a melancholy English Bohemian, capable of everything, except of living joyously on the surface.” [9]

PANURGE AMONG THE ORACLES

Yeats rather obsessively collected images of himself, [10] and had courted their variety. [11] Bewildered by the mirrors they offered into potential selves, he quarrelled with himself over which—and how many new ones—he would use, and whether to include any of the—by then iconic—images of his former selves familiar from his earlier books. Out went such admired portrait photographs as those by Elliot & Fry and Chancellor of Dublin. Which artists would he use for further new commissions? Who could be found to pay for them? What copyright questions might interpose themselves? Then there was the question of where they would be placed within the volumes—as a single sequence (a ‘fine sport to put Augustus Johns beside Shannons & Mancini beside my fathers’, he told Lady Gregory [12]) and, if so, in which volume—or deployed volume by volume in relation to the ordonnance of his various genres of writing. He was much exercised, too, by whether he could or should follow what he claimed was a French precedent and mix studio portrait photographs with original portraits. In a state of serial indecision, he sought opinion after opinion ‘like ‘Panurge consulting oracles as to whether he should get married’ as he wrote on another such occasion. [13] Invidious choices loomed, and quarrels focusing upon Mancini’s image broke out around him. John Butler Yeats wrote as early as 21 October 1907:

“I think you would make a serious mistake if you put Mancini’s portrait into your book, you are not a Caliban publishing a volume of decadent verse—nor are you in any movement of revolt that you should want to identify yourself in elaborate humility with the ugly and the disinherited.

Do you notice that in each of those three drawings at the Nassau, Mancini has put the left eye lower than the right—it has a curious ignobling effect. … He is a wit rather than a serious artist. A wit painter as Whistler is a poet painter and Sargent a prose painter.” [14]

To Lady Gregory, Yeats complained of Annie Horniman, the tea heiress who was bankrolling the new edition and who was a fellow member of the Order of the Golden Dawn,

“The Mancini she will not have but has taken August[u]s John into her family & is herself through Mrs MacEvoy trying to get the drawing out of him.” [15]

He rebuked his publisher, A. H. Bullen who had refused to accept either the Augustus John or the Mancini as frontispieces:

“The Mancini if you had enough knowledge of painting to see it is a great chance. It costs nothing & it is a master work by one of the greatest of living painters. I object to Miss Horniman being consulted. I have know[n] have [for her] many years & she respects me because I follow my own opinions and not hers in questions of this kind. The A[u]gustus John is a wonderful etching but fanciful as portrait. But remember that all fine artistic work is received with an outcry with hatred even. Suspect all work that is not. The one thing I will not have is sentimental representations of my self alone.” [16]

For a while, he thought he had worked around Bullen’s objections by proposing to group all the images together in one volume, perhaps with a new essay upon them, writing to John Quinn:

“I am going to put half a dozen portraits one after the other, A.B.C.D. They will come in the last volume. Its the only way out of the difficulty, Augustus John having made me such a ruffian, and my publisher in any case refusing both the John and Mancini as a frontispiece. I have got in both by this arrangement. I sat to Shannon before I left London, but don’t know when I shall be able to get back there for him to finish.” [17]

PERSONAGES

A clear-out of older portraits of Yeats’s younger selves was indicated, including all but one by his father, who had been doing frontispiece portraits of the poet since his first publication, Mosada, in 1886. With his publisher, Yeats was emphatic: ‘I will not have my fathers alone, or alone in Vol 1 because he has always schmalolzed me’ he wrote, conjuring a new verb from his reaction to the work of the sentimental sub-Pre-Raphaelite, Herbert Gustave Schmalz. [18]

“I have had strange adventures in trying to get a suitable portrait. My father always sees me through a mist of domestic emotion, or so I think, … I am going to put the lot one after the other, my father’s emaciated portrait that was frontispiece for the “tables of the law” beside Mancini’s brazen image and Augustus John’s tinker, to pluck the nose of Shannon’s idealist, nobody will believe they are the same man, and I shall write an essay upon them and describe them as all the different personages that I have dreamt of being, but have never had the time for.” [19]

Yeats slowly worked his way through this turmoil of indecision like a fretful algorithm.

- I have practically decided not to put the portraits all togeather, & to have only the Augustus John, the Sargent, the Mancini & the Shannon & perhaps the Coburn. Possibly I may ask Mr Bullen to hold over the Coburn photo for another book but I am not sure. I feal that these four portraits being the work of four of the greatest living masters will give the edition great importance. I dont want to dilute the effect. I keep worrying about putting in the Coburn. The getting of the Sargent has I think made a great difference. [20]

Mancini’s pastel eventually triumphed over the treasured photograph by Alvin Langdon Coburn—later frontispiece to Poems: Second Series (1909. Deciding against a new photograph—its slight blurring conveying the movement of his lips as he read aloud—Yeats preferred the Mancini’s pastel which caught his whole face in movement and animation. In doing so, Mancini may be said to have ‘drawn’ even more than the voice of a writer who insisted on ‘the living voice’. [21]

Mancini’s ‘Italian bandit’ also eventually triumphed, too, over Augustus John’s ‘tinker’. ‘I confess I shrink from the John thing’, he wrote to Florence Farr. [22] Musing in front of the mirror in 1930, Yeats remembered it:

“When I was painted by John years ago, and saw for the first time the portrait (or rather the etching taken from it) now in a Birmingham gallery, I shuddered.

Always particular about my clothes, never dissipated, never unshaven except during illness, I saw myself there an unshaven, drunken bar-tender, and then I began to feel John had found something that he liked in me, something closer than character, and by that very transformation made it visible. He had found Anglo-Irish solitude, a solitude I have made for myself, an outlawed solitude.” [23]

Among other portraits eventually not included were William Rothenstein’s 1898 portrait drawing (now in the British Museum), a photograph of a new bronze bust of Yeats by Kathleen Bruce, and a new drawing by Charles Shannon:

“very charming, but by an unlucky accident most damnably like Keats. If I publish it by itself, everybody will say that it is an affectation of mine.” [24]

In the end, sepia monochrome photogravures by Emery Walker of just four images were chosen as frontispieces. All revealed different aspects of Yeats’s ‘poet-posture’: the compound is Laura Riding’s. [25] For the first volume, containing all of his poems to date, a new 1908 charcoal drawing by John Singer Sargent became Yeats’s new auto-icon, the poet he felt himself now to be. [26] For the third volume (plays) a cropping was supplied from an ‘idealistic’ new oil portrait by Charles Shannon, removing a laurel wreath and psaltery, and if said Yeats ‘not flattering’ was at least ‘like’ him, a ‘very dark & old masterish’ image with ‘dignity & imagination’. [27] Mancini’s pastel opens the fifth volume, containing The Celtic Twilight and the Stories of Red Hanrahan, the demonic man confronting his enemies. Yeats was to write in that volume for John Quinn:

“if I only looked like the Manchini [sic] portrait I should have defeated all my enemies here in Dublin.” [28]

Emery Walker had insisted on making his photogravure reproduction from the original Mancini pastel. The plate-making had to await its being carefully couriered from Dublin to London to avoid a ‘shaking’. The delay meant that ‘[t]hat wretch Bullen’ had no option but to place it—inappropriately, Yeats thought—in the fifth volume to come off the press, ‘the least like it of all’. [29] Only in the seventh volume of further early stories did Yeats admit an image of a past self, a relatively under-used drawing by John Butler Yeats from 1896 originally done for the frontispiece of two privately printed stories, The Tables of the Law; and The Adoration of the Magi. [30]

Mancini’s pastel remained in Yeats’s possession and that of his descendants until September 1917. He never used it again, but his Italian translator, Carlo Linati, used it as frontispiece for two of Yeats’s books, Tragedie Irlandesi (Milano, 1914), and Lady Cathleen, 1892, L’Oriolo a Polvere, 1903 (Milano, 1944). Mancini’s Yeats became the poet’s face in Italy.

It has rarely been exhibited. Of the ‘Eighteenth Exhibition, Society of Portrait Painters, New Gallery, London, 6 November ‑ 29 December 1908, The Times commented

The two well‑known little heads of Browning and Mrs. Swinburne, painted long ago by Rossetti, will be seen again with pleasure; they form a pleasant contrast to the caricature of a poet of to‑day which some votaries of Signor Mancini will doubtless profess to admire. [31]

‘Studio‑Talk: London’ was more positive: ‘A deftly drawn face by A. Mancini is a notable feature of the south room, where there is also a portrait of Swinburne, lent by Mrs. Fairfax Murray.’ [32]

Confronting so many images of his updated selves reinforced Yeats’s disturbingly theatrical concept of the self, an essential notion in his occult theories of the Mask. Writing to a mistress of the time, Mabel Dickinson, he said:

“When I see you I will spread before you a whole array of portraits — Shannons, Sargents, Johns, my fathers, Mancinis & you shall take your choice. I belong to Augustus John at present but Mancini when I remember my enemies & Sargent when you have paid me a compliment. The ancient people were always actors & they could be any portrait they pleased, (seem it & then become it) — and that is the heroic life. We lose all in the pursuit of ourselves — a thing that does not exist.” [33]

© Warwick Gould

Institute of English Studies, London

17-06-18

[1] The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, ed. Peter Allt and Russell K. Alspach (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1957, 1966), p. 602. Warwick Gould gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Yeats scholars John Kelly, William H. O’Donnell and Deirdre Toomey in the compilation of these notes.

[2] https://metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/21413?exhibitionId=%7B4F31BE4C-309F-4A01-8A69-45D80D786215%7D&%3Boid=21413

[3] Such grid lines are much in evidence in other portraits, e.g., those of Lady Gregory and of Mrs [Ruth] Shine, Hugh Lane’s sister, also in the Dublin City Gallery. Other Mancini works now in the Hugh Lane Gallery include several self-portraits, Sylvia Hunter, daughter of his patron, Charles Hunter. Some were commissioned for the Gallery, others came as part of the Lane bequest of 1913, others added since then, now a total of 18 Mancini works.

[4] In all likelihood, Albrecht Durer. See his ‘A draughtsman drawing a portrait’ (1532), Victoria and Albert Museum, E.44-1894.

[5] Lady Gregory recalls her own session with Mancini and records Yeats’s account of his sitting in her Sir Hugh Lane: His Life and Legacy (1921; rpt. with a foreword by James White, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, New York: OUP, 1973) 79-80.

[6] Allan Wade, A Bibliography of the Writings of W. B. Yeats (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1951, 3rd edition, 1968), 87 & ff.: see also Collected Letters of WBY (Oxford: Clarendon, Vol 4, 737-38.

[7] ALS to Lady Gregory, 14 December 1907, Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

[8] Letter to John Quinn, 4 October 1907; The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats: Volume 4, 1905-1907 ed. John Kelly and Ronald Schuchard (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005), 739, hereafter CL4.

[9] TLS to John Quinn, 7th January 1908, Berg Collection, NYPL.

[10] According to William H. O’Donnell, he owned 49 portraits or reproductions of portraits of himself. See O’Donnell’s ‘Portraits of W. B. Yeats: This Picture in the Mind’s Eye’, Yeats Annual 3, 1985, 81-98 (89).

[11] See Letters to Lady Gregory, 18 December 1907, CL4 798, 803.

[12] See ALS to Lady Gregory, 6 January 1908, Berg Collection, NYPL.

[13] The Variorum Edition of the Plays of W. B. Yeats, ed. Russell K. Alspach, assisted by Catherine C. Alspach (London and New York: Macmillan, 1966), 1309-10. For the ‘French precedent’ see ALS to A. H. Bullen, 1 March 1908, Spencer Library, Kansas.

[14] John Butler Yeats, Letters to his Son W. B. Yeats and Others edited with a memoir by Joseph Hone and a preface by Oliver Elton (London: Faber and Faber, 1944), p. 102.

[15] ALS Berg Collection, NYPL, with envelope postmarked ‘LONDON 9 DE 07’, CL4. Other volumes are cited below as CL1, 2, etc..Horniman had chided Yeats’s spelling: ‘M A N C I N I is pronounced Manchini. If spelled in Italian with an “h” it would be pronounced Manheenee.… I congratulate him if he has put the “irate Demon” on paper!’ (‘Demon est Deus Inversus’ being Yeats’s motto in the Order of the Golden Dawn, and ‘My dear Demon’ her usual form of address).She threatened to destroy John’s etched plate (see CL4 798) but eventually compromised, suggesting that both the Augustus John and Mancini images be included: see NLI MS 13068 (7).

[16] TLS to John Quinn, 7 February 1908, NYPL; ALS to A. H. Bullen, 6 March 1908, Spencer Library, Kansas.

[17] TLS, NYPL, postmarked 8 February 1908.

[18] Schmalz (1856-1935) his name a condign punishment, later became Carmichael: A ‘good hearted vain empty man’, Yeats called him, after an 1887 visit to Schmalz’s studio (CL1 16).

[19] TLS to John Quinn, 7 January 1908, Berg Collection, NYPL.

[20] ALS to Edith Lister, 19 April 1908, Spencer Library, Kansas.

[21] See ‘Literature and the Living Voice’ in Explorations, sel. Mrs W. B. Yeats (London: Macmillan, 1962, New York: Macmillan, 1963), 202. Only a very few frames of Yeats’s face in motion survive, in a holiday maker’s silent home movie, shot in Algeciras in 1927, survive (In those images, Yeats and others are laughing and singing—a lip-reader has deciphered the utterance, ‘Happy Birthday to you!’.)

[22] ALS, 14 April 1914, Texas.

[23] Pages From A Diary Written In Nineteen Hundred And Thirty (Dublin: Cuala, 1944), 22. It too was used in a later book, A Vision (1937).

[24] TLS to John Quinn, 7 January 1908, NYPL.

[25] ALS to Warwick Gould, 1985.

[26] See frontispiece to Mythologies, ed. Warwick Gould & Deirdre Toomey (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

[27] ALS to Lady Gregory, 10 April 1908, Berg Collection, NYPL. Shannon’s painting, commissioned and paid for by John Quinn, is now in the Houghton Library, Harvard.

[28] Allan Wade, Bibliography (see above n. 4), p. 90; see also Complete Catalogue of the Library of John Quinn sold by auction in five parts [with printed prices] (New York: The Anderson Galleries, 1924), 2 v., p. 1146, lot 11495.

[29] ALS to Lady Gregory, postmark, ‘OC 6 08’, Berg Collection and letter to Emery Walker, 3 April 1908, Bucknell University.

[30] John Butler Yeats’s frontispieces, over-exposed largely because of the long-lasting Poems (1899) came to stand for the early Yeats.

[31] 5 November 1908, p. 8, col. 1. The Mancini pastel was item 619.

[32] The Studio, 45 (January 1909), 225. It was probably also shown at the 1961 Dublin Exhibition, ‘Images of a Poet’ (25). I am grateful to Professor O’Donnell for these exhibitions references.

[33] ALS to Mabel Dickinson, 10 August 1908, Bancroft Library, Berkeley.