The IES’s second Nineteenth Century Study Week (20-24 May 2019) focussed on the Brontës. Senate House Library selected a few items from its special collections to demonstrate to participants how library resources can support such work.

First editions give modern readers an insight into the experience of the initial readers of older texts. The existence of these in research libraries cannot be assumed: fiction before it becomes canonical is not a collecting focus of academic libraries, so that the presence of first editions of much English literature depends on the generosity of later collectors. The benefactor for the Brontës, as for much other English literature, was the EMI magnate Sir Louis Sterling (1879-1958), who collected first and fine editions of English literature and gave his books to the University of London in 1956. His gift enabled us to show the rather drab first edition of the Brontë sisters’ Poems (1846), in its original green cloth, albeit in one of the 961 copies reissued by Smith, Elder after Aylott & Jones had succeeded in selling only 39 copies. We also hold the first, three-volume editions of Charlotte’s novels, and brought out a volume of Villette (1853), which may strike the modern reader by its slimness and its generous line spacing for the exorbitant standard price of 10s.6d per volume.

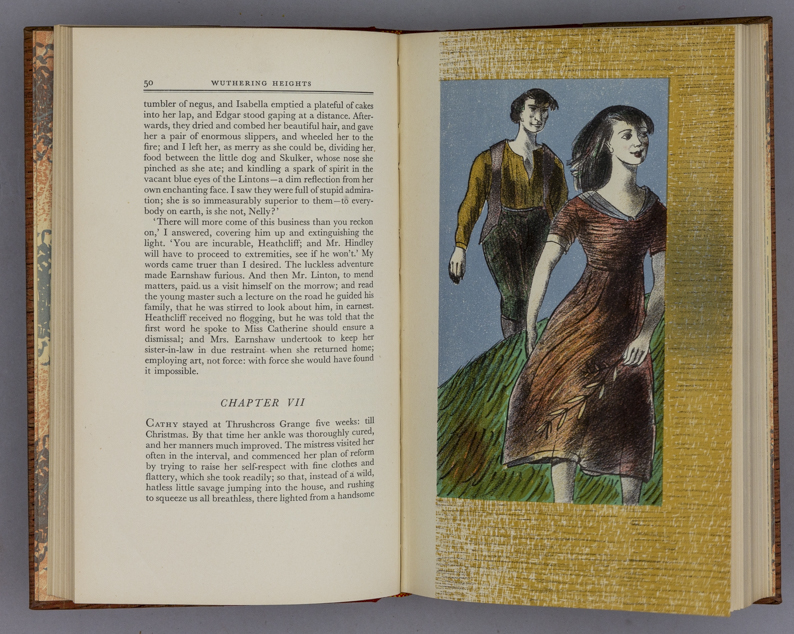

The Brontës’ works are not standard private press fare. But George Macy of New York published Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights at his Heritage Press, printed by the Curwen Press, which was reputed for its bookwork and decorated papers. Neither novel is considered easy to illustrate, but the Londoner Barnett Freedman (1901-1958) illustrated both with colour lithographs. The students pored over Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1940; another Sterling item) with its sixteen colour plates, mostly portraits of one or two characters against a minimal background.

Twentieth-century illustration, with the interpretation involved, is an aspect of reception theory. We highlighted a second facet of reception theory with a copy of Emma Jane Worboise’s Thornycroft Hall, first published in 1864. Although largely forgotten now, Worboise (1825-1887) was an extremely popular novelist in her time. Her evangelical message rendered her ‘sound’, as underlined in the bookplate in the Senate House Library copy declaring it to be a prize from the Salvation Army Young People’s War to Hedley Shay in 1906 ‘for good conduct, diligence and regular attendance’. Our copy is in fact from a small collection of prize books, given by a previous Librarian. Not only is the plot of an orphan unwanted by the relations bringing her up redolent of Jane Eyre, but Worboise draws explicit parallels. Her heroine and narrator, Ellen attends Castleton Bridge School:

“And now I am going to tell you something, though not much, of Casterton and of my life there; because, as you all know, Casterton is the ‘Lowood’ of that most powerful and world-renowned novel, ‘Jane Eyre’.”

She furthermore describes the Rev. Carus Wilson, Jane Eyre’s Mr. Brocklehurst, in terms of the earlier novel: “He was, as Jane Eyre tells us, a very tall man”.

And finally to background works. The Goldsmiths’ Library of Economic Literature, Senate House Library’s largest and most renowned special collection, is a treasure trove for works on the economic and social background of the industrial depression and textile industry. The book we chose to show was John Aikin’s Description of the Country from Thirty to Forty Miles round Manchester (1795) for a general description of the area in which the Brontës lived. The book is a bit early, certainly, but the detailed map naming Haworth seemed to excuse that. The actor Cecil Crofton (d. 1935) included in his collection of little books three editions of Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas from the teens of the nineteenth century. Compact and cheap, any one of these could plausibly have been the edition which Helen Burns in Jane Eyre carried around and read at Lowood – so out it came.

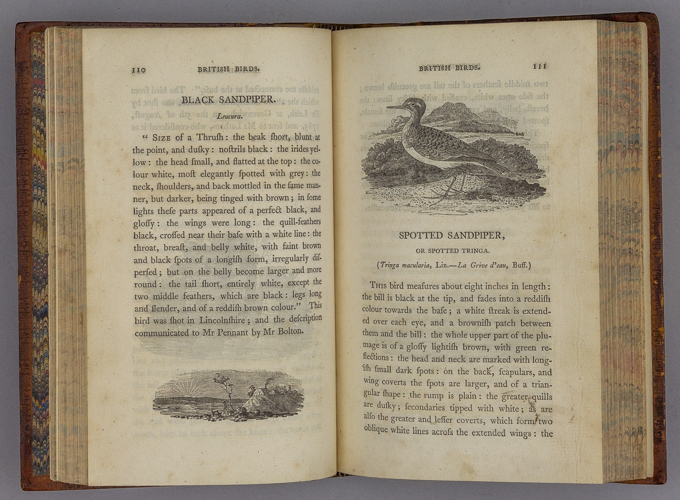

But perhaps the pièce de resistance was Thomas Bewick’s History of British Birds (1797-1804). We know that the Brontës owned a copy of this work, albeit in an edition from 1816; that the Rev. Patrick Brontë admired Bewick and that Charlotte Brontë wrote a poem, ‘Lines on the Celebrated Bewick’; and that Branwell, Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë all copied Bewick’s illustrations. Usually when we show this book to students as an artefact, we do so for its celebrated wood engravings as an illustrative technique. This time the physicality of the book took on new meaning, as students could see the size and feel the weight of the volume that Thomas Reed flung at Jane early in Jane Eyre. They could examine, too, the pictures that absorbed Jane, striking, if one has not seen Bewick before, for their smallness and for the fact that she is focussing on the ornamental tailpieces, not the larger pictures of birds described in the text.

“You are lucky to work with these books”, remarked a student upon leaving. As the Curator of Rare Books, I agree. We as a library are luckier still to see the books gaining new life, being used, and appreciated.

Dr Karen Attar

Curator of Rare Books and University Art, Senate House Library