Italian literature has long had a familiarity with pandemics. The first major Italian novel, Alessandro Manzoni’s I promessi sposi/The Betrothed was published in 1840 and is set during the plague epidemic of 1629-31 (you can read an 1844 English translation here: vol 1 and vol. 2).

Sally Blackburn-Daniels has discussed the pleasure of re-reading in her recent blog post. My pandemic meeting with Manzoni certainly falls under the label of re-reading. Like most Italians, I first read I promessi sposi as part of my school education. The status of “classic” weighed heavily on it and, while I admired the book, I could never get myself to love it. That is, until after leaving Italy, I was finally able to read it out of choice and not compulsion. Then it and other Italian classics became a way to remind myself that, whatever my circumstances, a part of me would always remain Italian.

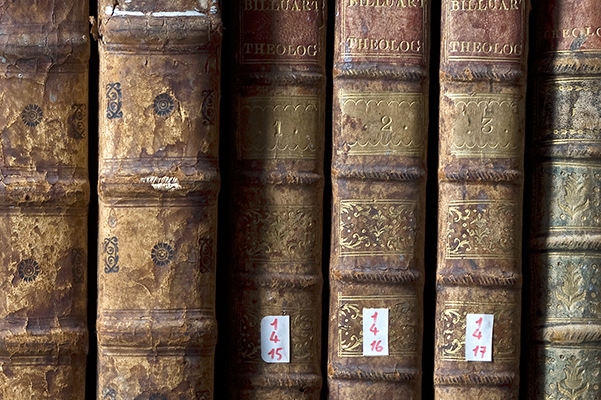

In his essay on “Why Read the Classics”, Italo Calvino argues that “a classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say”. Truly, with every re-reading, I took away something different from I promessi sposi, such as Manzoni’s invention of modern literary Italian, or the interplay of his text with the illustrations by Francesco Gonin. Would my pandemic reading of I promessi sposi reveal something new?

Most of Manzoni’s novel is dedicated to the misadventures of the titular betrothed, silk weavers Renzo and Lucia, beleaguered by dissolute nobleman Don Rodrigo and his sinister cast of allies. From Chapter XXXI onwards, however, the plague becomes the driving force of the novel. Manzoni assembles actual historical sources to document its appearance and progress within the Milanese state. When re-reading these chapters, I could not help but compare the actions of my ancestors with those of my contemporaries. These passages made for extremely uncomfortable reading. All the stages we experienced in the coronavirus pandemic are there in I promessi sposi: the first warnings from doctors being ignored; mass gatherings acting as “super-spreader” events; the authorities deliberately downplaying the seriousness of the situation; the disease being referred to as “pestilential fevers”, then as “a limited form of plague”, before the delayed recognition of the seriousness of the contagion; the health system being overwhelmed; thousands of families being locked down in the Lazzaretto (the quarantine station at the doors of Milan); unprecedented levels of mortality across the land.

The most disturbing part of my re-reading was, however, Manzoni’s account of the untori poisoners mass hysteria. Unable to explain the mechanics of the contagion and looking for scapegoats, the citizens of Milan begin to believe rumours about individuals who propagate the plague by anointing buildings and churches with oily poisons. Soon, suspicion and disinformation ravage the city, resulting in summary arrests, trials and executions, often accompanied by appalling uses of torture. Manzoni recounts the history of the most memorable case of untori persecution in the treatise Storia della colonna infame, originally published as an appendix to I promessi sposi. I remember reading both as a university student, taught by the great Ezio Raimondi, one of Manzoni’s finest commentators. At the time, I felt smugly superior to my credulous ancestors and secure in the knowledge that such episodes could never occur again in our more enlightened, scientific age. I should have recalled the words of another of Italy’s classics, Giacomo Leopardi’s 1836 poem La ginestra. In it, Leopardi mocks the “secol superbo e sciocco” (arrogant and foolish century) with its acritical belief in humanity’s “magnifiche sorti/e progressive” (magnificent and progressive futures). It turns out, human minds have not changed that much since the 1630s or even the 1830s. Despite higher literacy and education, we are still ready to believe in quack theories, spread disinformation and, what is worse, delay the enactment of those measures that can actually reduce the impact of the pandemic.

As I put the book down, I try to draw some hope from it. Despite the ravages of the plague, the protagonists Renzo and Lucia do survive and finally get married. The evil Don Rodrigo after denying its existence, succumbs to the disease alone, abandoned by all. It is in the plague chapters that I find Manzoni’s strongest call to action: to support the other members of our community in this time of need, as Manzoni shows through the widowed tradeswoman who helps Lucia in the Lazzaretto or the other examples of solidarity and generosity that dot the later sections of the novel. Most importantly, Manzoni reminds us to “observe, listen, compare, think, before speaking”, instead of spreading falsehood and division.

What a sobering conclusion to this pandemic foray into Italian literature! Of course, my bookshelf contains another pandemic classic, Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron. Perhaps this time I will come up with more cheerful reflections…but I will need to leave them for another post.

Works cited

- Manzoni, Alessandro, I Promessi Sposi. (Milan: Guglielmini and Redaelli, 1840)

- Calvino, Italo, ‘Why Read the Classics?’, New York Review of Books, 9 October 1986

- Leopardi, Giacomo, Canti (Florence: Felice LeMonnier, 1845)

Francesca Benatti is Research Fellow in Digital Humanities in the department of English and Creative Writing at The Open University. She has published on book history, Irish studies and comic books.