A couple of weeks ago I was asked to list a few of my favourite things. No, not raindrops on roses, whiskers on kittens, bright copper kettles, nor even warm woollen mittens. Brown paper packages tied up with strings come close to the mark, although the packages were unwrapped and their contents placed lovingly on shelves over 150 years ago by fingers long skeletal, for the request was to name and describe half a dozen of my favourite items among the books printed before 1601 in the library of Augustus De Morgan (1809-1871) at the University of London’s Senate House Library.

The appeal came in connection with Brill’s digitisation of the material for a full-text database. Yet it applies equally well in connection with a study of De Morgan’s reading for The Edinburgh History of Reading, edited by Mary Hammond and Jonathan Rose in 2020, to which I was one of four IES-related contributors. My chapter was about De Morgan’s reading and library. De Morgan collected books pertaining to mathematics, a subject with – let’s face it – limited general appeal. At an introduction to the Brill database a historian of mathematics revelled in the scientific landmarks of the collection, focussing the content, when asked for his favourites. I chose books from a book-historical viewpoint, demonstrating the fascination of books beyond their subject matter. Most of these appear in my chapter in the Edinburgh History. Here are four of them:

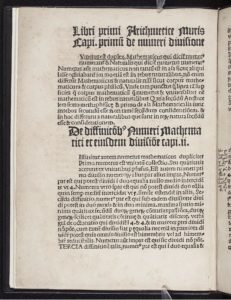

Johannes de Muris, Arithmetica speculativa [Central Germany: s.n., ca. 1520].

Johannes de Muris, Arithmetica speculativa [Central Germany: s.n., ca. 1520].

This 24-page quarto work is a little-known work of arithmetic, a mediaeval transmission of Boethius. This edition is extremely rare and possibly unique. It is a gift when discussing the artificiality of the distinction between incunabula and post-incunabula, as ambiguity surrounded the status of the work for many years. De Morgan in his bibliography of arithmetical books attributed it as being “certainly of the very earliest part of the sixteenth century, if not of the fifteenth”. Although twentieth-century specialists in incunabula thought it was more likely to have originated in the sixteenth than in the fifteenth century, the question was solved definitively only in 2012, when an expert from the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek noted that the round comma which appears here was unknown in the fifteenth century.

I feel that the work cries out to be delivered from obscurity with a translation and editorial comments. Mathematical medievalists searching for projects, where are you?

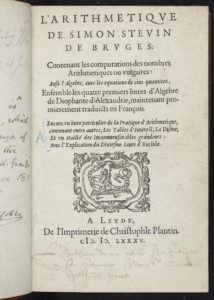

Simon Steven, L’arithmetique de Simon Steuin de Bruges (Leiden: C. Plantin, 1585)

Often when asked about their favourite books, librarians, like authors, nominate whatever they are working on at present. I have been working on Christophe Plantin, the 1520-born printer who with his heirs dominated northern European printing for over a century. This led me to select one of his productions. It is the landmark work of the Flemish mathematician and engineer Simon Stevin (1548-1620), L’arithmetique, which makes the first announcement of the use of decimal fractions.

Stevin authored five of the nine mathematical works that Plantin printed between 1560 and 1585. This is the second of them. It is also chronologically the second of five titles by Stevin owned by De Morgan, all from various publishers in Leiden or Antwerp. De Morgan approved of Stevin’s “originality, accompanied by a great want of the respect for authority which prevailed in his time”. De Morgan’s copy includes a title page inscription attributed tentatively by De Morgan to Stevin himself.

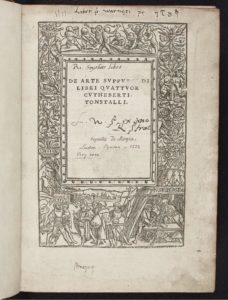

Cuthbert Tunstall, De arte supputandi libri quattuor Cutheberti Tonstalli (London: Richard Pynson, 1522)

Cuthbert Tunstall, De arte supputandi libri quattuor Cutheberti Tonstalli (London: Richard Pynson, 1522)

Patriotism leads me to favour this arithmetic book, as the first work printed in England devoted exclusively to mathematics, and, according to De Morgan in his arithmetical bibliography, a good one at that: “For plain common sense, well expressed, and learning most visible in the habits it had formed, Tonstall’s book has been rarely surpassed, and never in the subject of which it treats”.

The common sense arises perhaps from circumstances of the writing: thinking that he was being defrauded, Tunstall wrote the work for his own benefit in order to be able to check his accounts. The book’s glamour for a book historian is the printer, who along with William Caxton and Wynkyn de Worde was one of England’s three famous early printers. One of Richard Pynson’s achievements was to introduce roman type to England, as seen here. The detailed woodcut border on the title page is thought to be by Hans Holbein.

As a librarian, it is helpful to be able to show the book alongside other specimens of Pynson’s and Holbein’s work. And whatever one’s patriotic pride, it is also salutary to note how interwoven the European book scene was. Pynson (printer to Henry VIII) was a native of Normandy; Holbein was Dutch; Tunstall based his work on the arithmetic of the Italian Luca Pacioli (also represented in De Morgan’s library); and the text is of the first of three sixteenth-century editions of Tunstall in De Morgan’s library, with the second emanating from the Parisian scholar-printer Robert Etienne (1529).

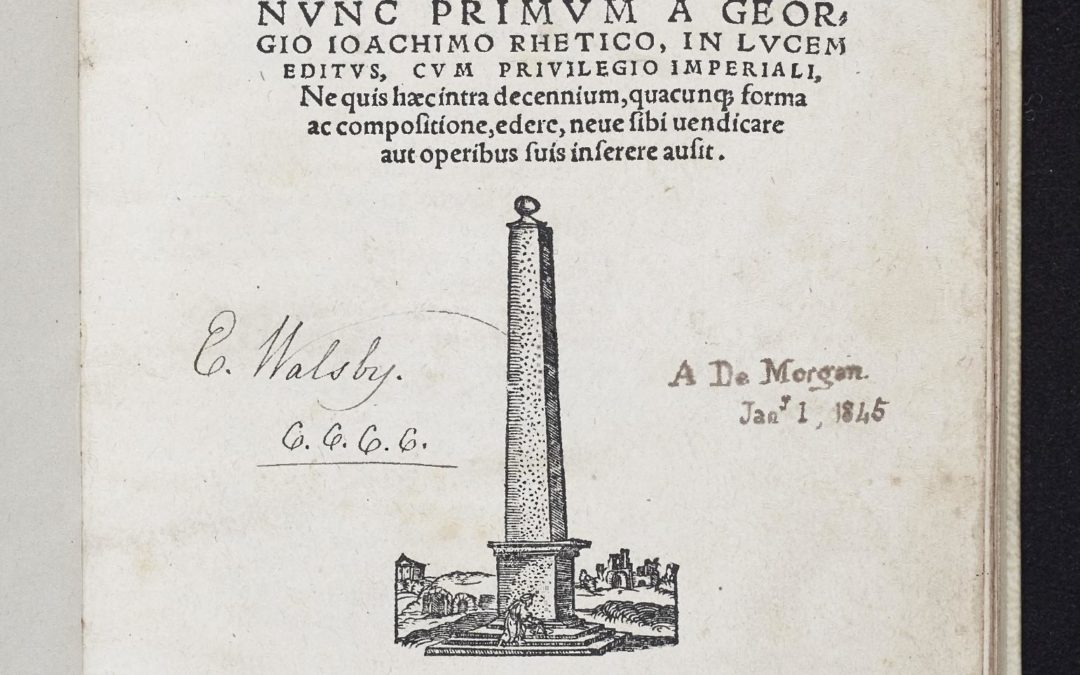

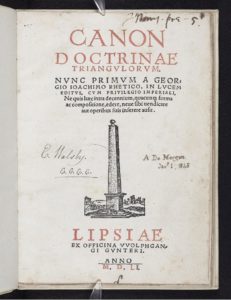

Georg Joachim Rhäticus, Canon doctrinae triangulorum (Leipzig: W. Günther,1551)

This brief work, printed in red and black, is the earliest complete publication of six-function trigonometric tables,. It is one of my favourites for De Morgan’s annotation about its acquisition (quoted also in the Edinburgh History of Reading):

This book was bought Jan 1 1845, out of the catalogue for 1845, sent me the day before. When I saw this, I was after it at once, and not too soon, for Babbage, who has a keen nose for a mathematical table, was an hour after me. He was a little vexed, but he afterwards acknowledged, when he saw my paper on the subject, that it was better in my hands than his, because I made it known.

The annotation, from July 1852, shows how he returned to his books. Reference to De Morgan’s paper provides an excellent example of the way a prominent Victorian collector used his books. The article in question, ‘On the Almost Total Disappearance of the Earliest Trigonometrical Canon’, appeared in 1845 in The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 26 (pp. 517-26). De Morgan pasted a copy of it at the back of the book, enabling posterity conveniently to read the book and De Morgan’s essay on it together.

I have favourite things relating to the articles of colleagues writing in the Edinburgh History of Reading too: for example, in connection with Simon Eliot’s chapter on the Ministry of Information, a MoI pamphlet in the Senate House Library collections rejoicing that an upside of the War was that the English were finally learning how to cook vegetables. But my colleagues must speak for themselves.

Dr Karen Attar is Curator of Rare Books and University Art at Senate House Library, and a Research Fellow in the Institute of English Studies.