On the 138th birthday of Milanese industrialist, publisher and bibliophile Giovanni Tréccani, CULTIVATE MSS’s Dr Federico Botana traces the European travels of one of Italy’s most celebrated Renaissance manuscripts – revealing how Tréccani’s persuasive talents, a frantic dash to Paris and an intervention from Mussolini resulted in its purchase for the nation.

Understanding how and why medieval manuscripts acquired the status of cultural monuments in an era of increasing nationalism is one of the aims of the ERC-funded CULTIVATE MSS project, based in the IES. A remarkable example is the return to Italy of what politician and amateur art historian Pietro Niccolini called ‘the most beautiful manuscript in the world’, the Bible of Borso d’Este, in 1923.

The events were reported in detail in the April-May 1923 issue of La Bibliofilia, the journal founded and directed by the erudite bookdealer Leo S. Olschki. The protagonists of the story include: Zita of Bourbon-Parma, the last empress of Austria; Giovanni Tréccani, a wealthy Milanese industrialist and publisher; Tammaro De Marinis, a famous Italian bookdealer; an unnamed friend of De Marinis (apparently, a well-known figure in Parisian artistic circles); a greedy Parisian antique dealer (also unnamed); and Benito Mussolini.

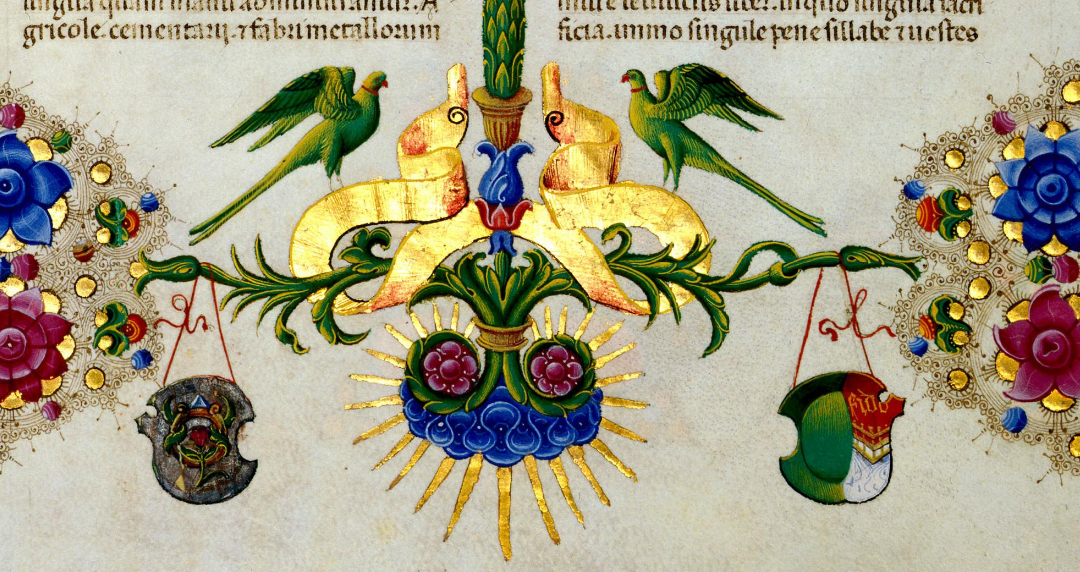

The Bible was commissioned by Borso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, in 1455. It took ten years to be completed and is in two volumes, each of about three hundred folios, including a thousand miniatures. The borders of every page are decorated with jewels, dragons, golden putti, iridescent chimeras and anything the vivid imagination of Taddeo Crivelli, the main illuminator of the Bible, could produce. In 1796, fearing the imminent arrival of the Napoleonic army, Duke Ercole III d’Este fled to Venice carrying the Bible, which then ended up in Vienna in the library of his daughter, Maria Beatrice, archduchess of Austria-Este. In 1831, the Bible returned to Modena (the capital of the Duchy of Este from 1598), only to leave for Vienna again in 1859, as the last Este duke, Francesco IV, fled Garibaldi’s republican army.

The manuscript reappeared in Paris in April 1923. Zita, dethroned and in need of cash, sold Borso’s Bible to an antique dealer. As we learn in La Bibliofilia, the bookdealer De Marinis heard from his friend that the Bible was about to be shipped to a rich banker in the United States. He rushed to Paris, convinced the new owner to halt the sale until the end of the month, and flew to Rome to ask the government to intervene.

De Marinis then discussed the matter with Mussolini in person, but the sum wanted by the Parisian bookdealer was astronomical: four million Francs! Mussolini summoned Tréccani and told him that it was imperative to stop Borso’s Bible suffering the fate of so many great Italian works of art: entering the collection of an American millionaire.

Tréccani agreed to help, sending De Marinis to beg the Parisian bookdealer to wait for another day whilst he raised the money in Milan. Once in Paris, with the help of De Marinis and his friend, Tréccani convinced the bookdealer to accept 3,300,000 Francs by declaring his intention of donating the Bible to the Italian nation. Meanwhile, De Marinis’ artistic friend argued that if the Bible went to Italy, it would remain in Europe and French scholars could study the manuscript too. If instead, the manuscript emigrated to America, it would disappear forever!

The success of De Marinis’s and Tréccani’s mission had a special significance in the political context of 1920s Italy. Like other European nations, Italy was still recovering from First World War. More importantly, Italy was a new nation: it had been unified into a single state only in 1861. Recovering one of the great artistic treasures of the Renaissance, culturally the most prestigious period in the history of the peninsula, was a matter of pride not only for the new nation, but also for the former Este territories, which had been under Austrian rule in the nineteenth century. Borso’s Bible was produced in Ferrara, but despite the pleas of some of the city’s notables, the government decided that the Bible should return to Modena, the last capital of the Duchy of Este.

On 25 July 1923, in a ceremony attended by members of the government and officers of the Reali Carabinieri, the Bible was restored to the Biblioteca Estense at Modena. It was installed in a glass cabinet, where it can still be appreciated today, flanked by golden busts of of Borso d’Este and Giovanni Tréccani.

Image credit: The Bible of Borso d’Este, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena, Ms. Lat. 422-423, fol. 3r, detail.

CULTIVATE MSS, funded by the European Research Council, explores how the trade in medieval manuscripts between 1900 and 1945 affected the development of ideas about the nature and value of European culture during this period. Follow the project on Twitter @cultivate_mss.