Cynthia Johnston

In preparation for a series of broadcasts for BBC Radio Lancaster’s Museums’ Week in November, I visited the Harris Museum and Art Gallery in Preston last week. The Harris holds a spectacular collection of rare books comprised of several discrete bequests: the Sheperd Library, originally an 18th century collection greatly enhanced during the 19th century, the Spencer Collection of Children’s Books and the Francis Thompson Collection, both the gifts of the same patron, and a fine collection of Private Press books donated by Joseph Pomfret a former librarian (1878-1944). The Harris Museum’s Special Collections also contain impressive complete runs of many Victorian periodicals including All the Year Round, the Athenaeum, and Blackwood’s Magazine.

With the exception of the Sheperd Library, these collections, and the Harris Museum itself, were created from wealth accumulated during the Industrial Revolution. The interests reflected in the collections are diverse, but despite their broad intellectual and social historical reaches, all were thought worthy of donating to the public library of the town.

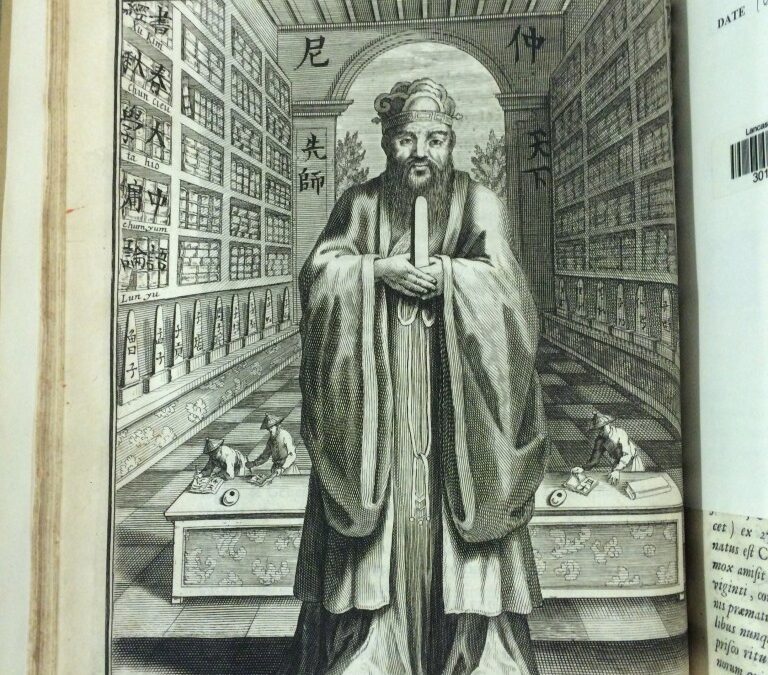

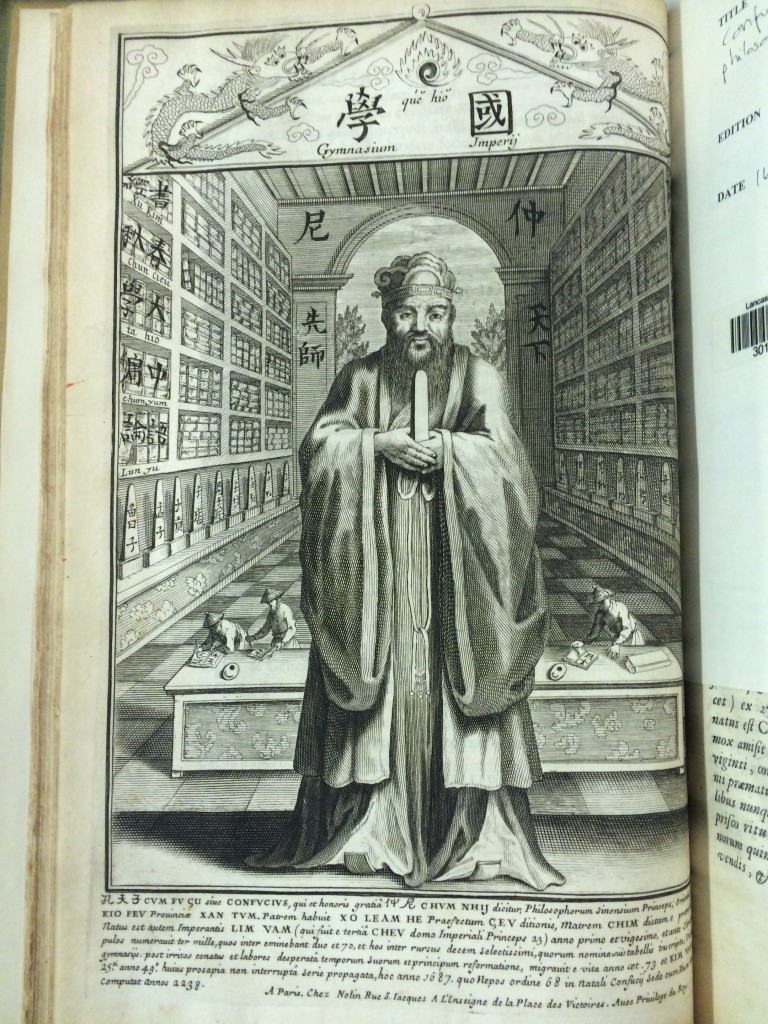

The Sheperd Collection holds outstanding examples of early printing. Sheperd was a local physician and twice mayor of Preston. His library originally comprised several thousand volumes. It was expanded by bequests and acquisitions in the nineteenth century and now holds over 10,000 volumes. Highlights include the first translation of Confucius into English:

Confucius Sinarum philosophus: sive scientia Sinensis Latine exposita / stu . – Parisiis : Apud Danielem Horthemels…, 1687

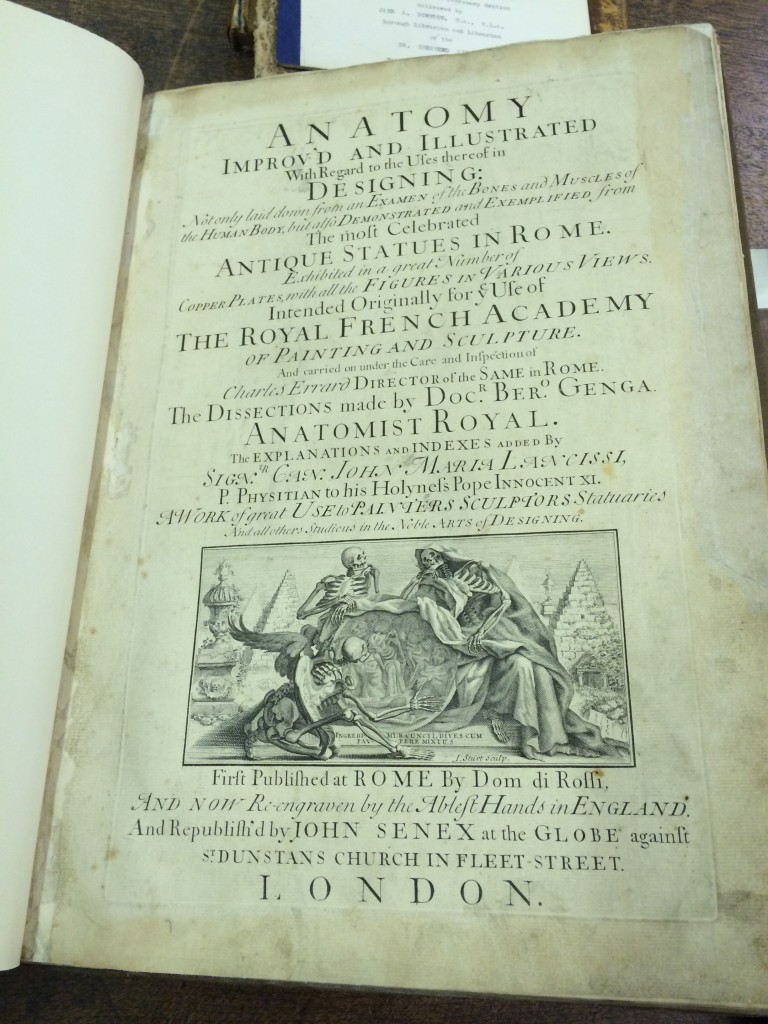

Sheperd’s vocational interests are well represented in his collection including one of the first printed books on anatomy, Charles Errard’s Anatomy (London: J. Senex, 1723).

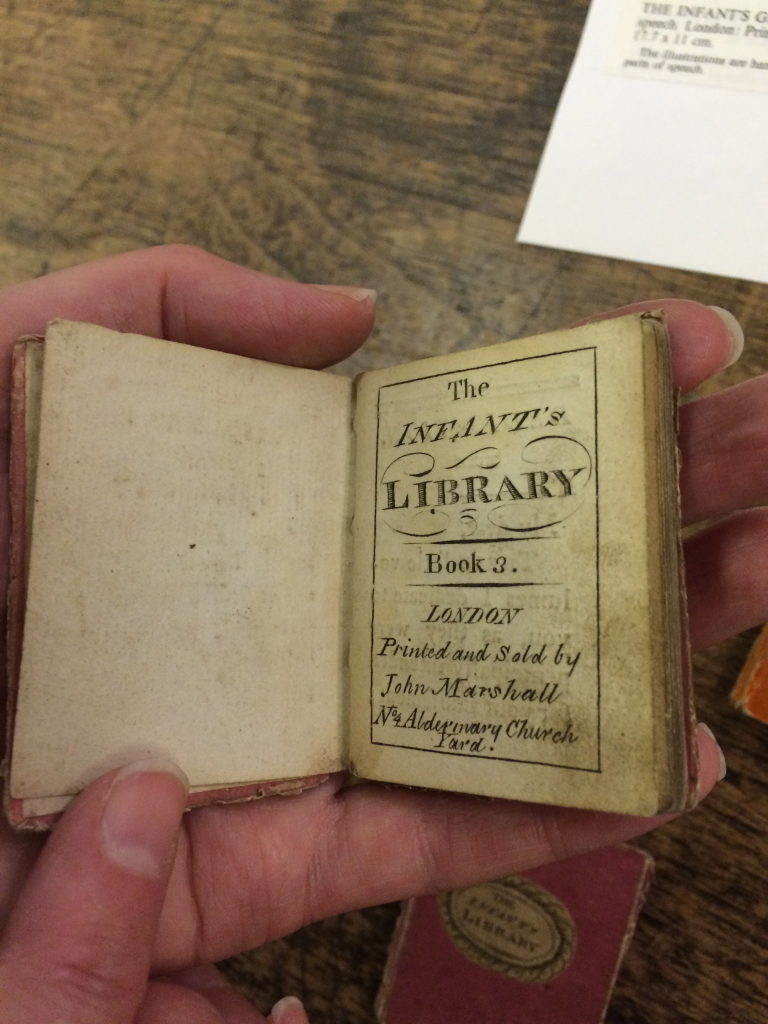

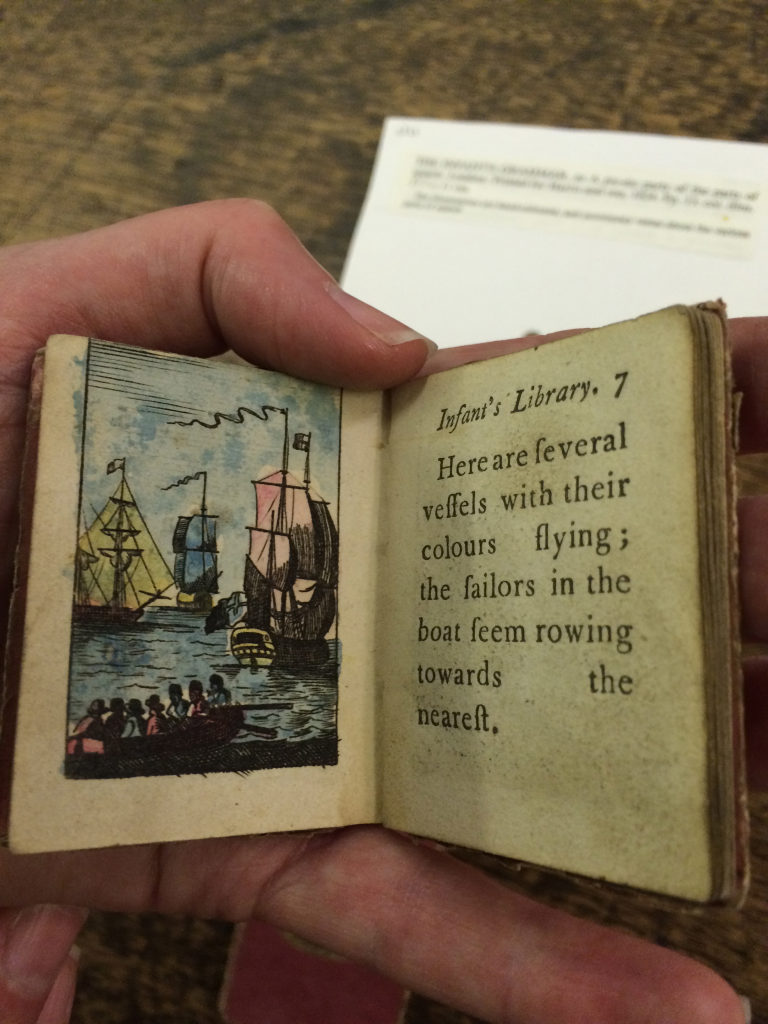

John Henry Spencer was born in 1875 and began his life working in the cotton mills. He eventually became assistant secretary of the mill. He had a passionate interest in the history of Preston, and his collection of children’s books is exceptional. Highlights include the Infant’s Library, published in London between 1785 and 1802. A note inside the book below reads, ‘reads ‘Printed in 1802. Given to me when 4 years old. Now I am 73. Mary Lane, Decr. 29th, 1871′.

While the Harris Collection has been immaculately catalogued and conserved by the Museum’s curator of Special Collections, Anna Crouch, over the past decade, it has been the subject of little academic research. There are many rich seams to pursue here. Beyond the contents of the collections themselves lies the overriding question of the purpose of these public bequests in the context of the new Cotton Towns. This is the question Ruskin posited, ‘For what purpose do they spend?’ Surely an answer lies in the examination of these collections in their larger regional and socio-historical context.