In this week-long exploration of Sir Thomas Phillipps’ manuscripts and their fate, Dr Hannah Morcos investigates the attempts to repatriate French manuscripts from the Phillipps collection.

A significant proportion of the manuscripts amassed by Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872) were made or acquired in France, ranging from important medieval cartularies to letters from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Phillipps profited from the wealth of material on the market in the nineteenth century. Motivated by his own archivistic intentions, the self-proclaimed ‘perfect vello-maniac’ was insatiable, buying as much as he could grasp. He scooped up lots at auctions of collections rich in manuscripts from dispersed religious libraries. Simultaneously, he took advantage of the French archives and libraries willing to sell off little-valued older items in order to buy new books. He also obtained French items from the libraries of other English collectors, including that of Richard Heber (1773-1833).

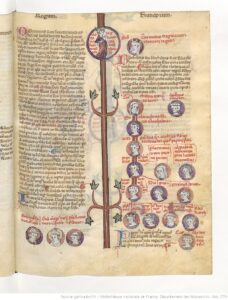

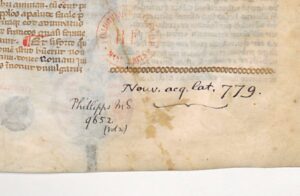

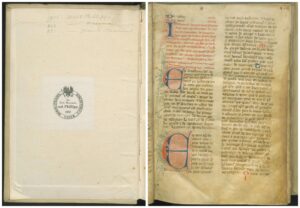

Bernardi Guidonis Flores chronicorum usque ad annum 1331 (14th-century, France), obtained by Phillipps from the Heber collection and acquired by the Bibliothèque nationale at the Phillipps sale in 1903 (lot 519) (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS NAL 779 (fols 170r and 167r).

When it came to assuring the future of his incredible collection, Phillipps was unable (or perhaps unwilling) to form an agreement to leave it to either the British Museum or the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Instead, the onerous and expensive task of maintaining his enormous library and home was bequeathed to his daughter Katharine Fenwick (1823-1913) and her husband.

In addition to numerous auctions, the Fenwicks agreed many direct purchases with institutions and private collectors. Some European governments were quicker off the mark than others to stake their claim on items in the collection. In 1887, the Royal Library in Berlin acquired the majority of the Meerman collection, including manuscripts formerly held by the Collège de Clermont in Paris much to the chagrin of the French. In the following year, the Dutch and Belgian national libraries also negotiated purchases relevant to the history of each nation.

French translation of Ramon Llull’s Llibre d’Evast e Blaquerna (14th-century, Paris), now Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Ms. Phill. 1911, with Meerman-Phillipps-Berlin book plate.

The French watched on with ‘interest and anxiety’ (Bibliothèque de l’école des chartes (1888), p. 694). They were not in a position to act as swiftly, hindered perhaps by budget, the sheer wealth of relevant manuscripts, and a longstanding attempt to buy back 166 manuscripts stolen from the French national library and (unwittingly) acquired by the Earl of Ashburnham.

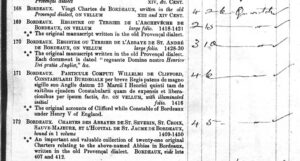

At the Phillipps auction in 1903, the Bibliothèque nationale de France acquired 114 manuscripts via the London-based dealer Quaritch, in addition to several items bought for the Archives de la Gironde, Bordeaux (pictured above). Then in 1908, following years of negotiations with Phillipps’ grandson, Thomas FitzRoy Fenwick (1856-1938), Henri Omont, the Bibliothèque nationale’s curator of manuscripts, secured the purchase of 272 manuscripts en bloc.

This major acquisition of primarily medieval historical documents was supported by contributions from three high-profile private collectors: Thérèse de Rothschild (1847-1931), Edmond de Rothschild (1845-1934) and Maurice Fenaille (1855-1937). Thérèse de Rothschild’s donation included two important cartularies, from the abbey of Saint-Quentin in Beauvais (twelfth-century) and the Templiers of Sommereux (thirteenth-century).

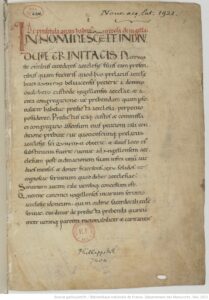

Cartulary of the abbey of Saint-Quentin in Beauvais, one of the Phillipps manuscripts gifted to the Bibliothèque nationale de France by Thérèse de Rothschild in 1908 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAL 1921, fol. 1r).

Henri Omont was lauded in the press for his heroic role in the manuscripts eventual return, as were the private donors who contributed to ‘cette patriotique œuvre de sauvetage’ (Le Temps, 8 May 1908). Phillipps may have believed that he was safeguarding their preservation. For the French, however, the exodus of these manuscripts became a source of national regret that extended beyond scholarly circles. Following the scandal of the stolen Ashburnham manuscripts, the curators at the Bibliothèque nationale de France were more determined than ever to repatriate the most significant of ‘their’ patrimonial artefacts in the Phillipps collection, rather than risk losing again these objects of ‘inestimable’ value to France.

Follow @cultivate_mss for more on Phillipps and his manuscripts.