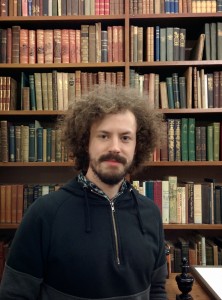

My name is Benjamin Maggs, and I am not a bookseller. Imagine this spoken in the hushed tones of an introduction at a self help group, or an embarrassing secret whispered by an elderly relative. I feel guilty and ungrateful; but let me explain.

I come from a family of booksellers that began, in bookselling terms, in 1853 with the founding of Maggs Bros. by the fabulously named Uriah Maggs, a name which only becomes more fabulous in translation from the Hebrew as “Flame of God” but which has, it must be said, done nothing for the inferiority complex of his descendents. This was the same year as the founding of the Levi Strauss Company, the capture of Nanjing by the army of Hong Xiuquan in the Taiping Rebellion, one of the bloodiest conflicts in history, and the opening of the first passenger railway in India. Maggs continues in family hands today and is one of the rare survivors of family management in a trade in which almost all of the protagonists are named after their founders but few have retained the tribal connection.

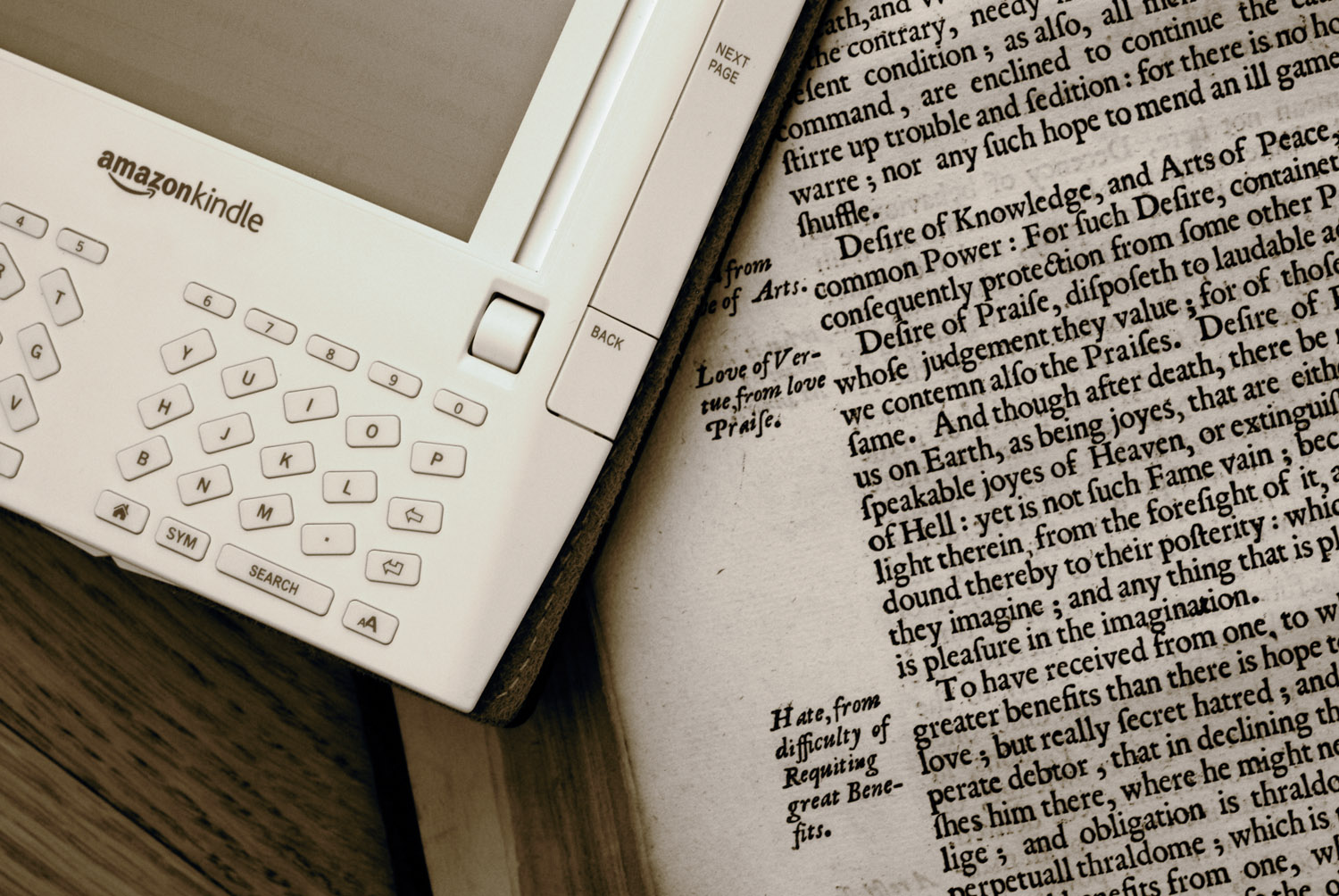

I was born in the late eighties and grew up, as much as I ever will, in the nineties and naughties, which makes me a millenial, a member of the first generation to grow up with widespread digital technology, a digital native. It wasn’t that I didn’t enjoy reading and owning books, but rather that they seemed so frustratingly inefficient to a person who lived in the heady days of Napster and an all-you-can-eat 56k modem, which had just been freed from the tyranny of charging by the minute. I remember asking my dad why I couldn’t download books like I could music and he explained to me, with I think a dash of wishful myopia, that people had tried it and it hadn’t worked: the Rocketbook and the eBookman were too far ahead of their time. But it was only a matter of time; Amazon launched the Kindle in 2007, a device which looked like it had been taken straight from the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and ebooks hit the mainstream.

My precocious question about ebooks betrays a youth spent in the ‘constant present’ of a virtual universe that is ‘our equivalent of the mare incognitum, the unknown sea that lured ancient travellers with the temptation of discovery. Immaterial as water, too vast for any mortal apprehension’ (Alberto Manguel, The Library at Night, p.28). With texts delivered without context and always available, each one given equal weight in a flattened hierarchy of knowledge, scarcity of data and the privilege of one book over another were foreign concepts to me. This was always going to make my relationship with the world of antiquarian books a difficult one.

While the age of the internet had a great influence on my sense of the immaterial text I realise that the rejection of the physical is only the natural continuation of a programme of commodification which has, in one form or another, probably accompanied the book from the very beginning. The modern book is very much the quintessential finished product; its origins are obfuscated, its binding ‘perfectly’ hides the manufacturing processes and the printing leaves no tactile trace, as if the ink floats on the surface of the paper. From an early age I was inoculated against the reality of the book as a built object, the culmination of manifold intricate processes and the inheritor of a long history of development.

The result was that when I started working at the family business in the beginning of this year as a general dogsbody I knew hardly anything about the world that it operated within. My goal in studying the History of the Book at the Institute of English Studies is to take the single point in time that is the finished book and stretch it into a line, to go backwards and perhaps forwards in time to understand the processes that have created it and the developments that have shaped it into what we now know. As I have progressed in this term I have found a world of book production that is at times both more and less familiar then I expected, and had the chance to interact with the physical book in ways that have shown me its ability to act as a time capsule which can tell us much more about the people who made it than I had imagined.

I hope that, with the help of this course, my tutors and the friends I have made through it, I might be allowed to append my introduction:

“My name is Benjamin Maggs and I am not a bookseller. Yet.”

Benjamin Maggs is a masters student reading History of the Book at the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is writing a series of three blog posts for the school exploring his experience of the course and his reasons for studying the subject.

I fell across your article on line and found it of great interest.

I am researching the family of Charles Maggs (1849) and Alice Maggs, brother and sister who married into a local farming family in Melksham Wilts in 1871. Charles inherited a rope and tarpaulin factory from his father Joseph H Maggs and later started Wiltshire United Dairies. His son grew it into United Dairies and had the knickname of “Mr Milk” in London at the turn of the 19th/20th century.

It is now known as Unigate St Ivel.

A younger brother named Joseph Henry Maggs attracted my attention as he married a girl from Shrewsbury in 1879 in Wolverhampton.

Upon checking his occupation he was a bookseller.

Some time later,tracing the family back I got to Midsomer Norton and Uriah Maggs. I have not established a direct link but am getting close.

If you come across any information regarding the parents of Uriah Maggs I would be grateful.

How did Joseph Maggs get to Wolverhampton?

The GWR opened tracks to Wolverhampton circa 1854, my great uncle was a driver and was found in lodgings in Wolverhampton in the 1861 census. The line went on to Shropshire and Wales.

If you are interested further I have an Ancestry tree of which Maggs are a part.

Best Regards, C.Harris