Mena Mitrano (Loyola University Chicago, Rome Center) participated in the T.S. Eliot International Summer School (11-19 July 2015).

Encountering T. S. Eliot again at the 2015 Summer School has meant for me receiving a major re-introduction to the art of giving.

The first gift is what might be called room for “breathing.” It refers to a state of well being that comes from inhabiting a space that is, of course, material (Senate House, the building where the Summer School was held on the West side of Russell Square close to where Eliot worked at Faber and Faber), but also densely symbolic, made up of words and ideas as well as presences, forms of contact, layers of communication other than linguistic, all of which immersed participants in the Eliot vocabulary and in his world. As an outcome of such hospitality, one realizes what an incredible opportunity Eliot is for thinking and for writing today. That room for breathing should be had not only by those who have come encouraged, perhaps, by their connections or even discipleship to Eliot scholars but also, and quite powerfully, by scholars from diverse backgrounds, and with diverse interests and modernist or theoretical genealogies, is quite exceptional and, I would say, the trademark of the Eliot Summer School.

The lectures by prominent Eliot specialists are a first-hand introduction to the debates in the field. In step with the new archival materials made available in the online edition of The Complete Prose edited by Ron Schuchard and his team, together with recent studies such as Robert Crawford’s Young Eliot (March 2015), at this year’s school the sense of an opening, the inauguration of a new era in Eliot studies was palpable. As Ron Schuchard told us, this is an exciting time to be studying Eliot. As he prodded us to explore and use the range of resources, he inspired us to entertain the promise that Eliot is enabling us, somehow, to say what we might not be able to say via other means and from other vantage points.

The visits to the locations of The Four Quartets remain impressed on my mind as an example of how a poet can indeed take us on his journey and how this journey can intersect with ours. The beauty felt at Burnt Norton, Little Gidding or East Coker cannot be explained merely but the interesting layers that our presence in those places might add to our reading of Eliot’s text. We were not there, it seemed, to hoard and acquire new clues to reading (although, perhaps, in this case, that sort of expectation might be justified); rather, the experience of this beauty is inseparable from the intimation of a clearing or new space, so that one can really grasp what Lyndall Gordon means when she asks: How does Eliot transcend time? How does he touch other lives?

At a certain point in his life Eliot decided that he belonged to London. With the city, he chose entanglement in the world of nine-to-five work, the discipline necessary to combine a job done for money with the life of the mind, his hard and serious academic work as an extension lecturer, the conflicts and compromises that transformed the talented poet into an influential public intellectual. What limited time he had available to himself he had to use wisely and work out those questions that really needed to be asked. Especially when compared to Wallace Stevens (as I did in Massimo Bacigalupo’s seminar), T. S. Eliot might uncannily appear as our contemporary. Eliot’s form of life–with its knot of work, thinking, human desire and moral questions–feels incredibly close to our times of generalized economic hardships and, within the Humanities, struggle for critical renewal.

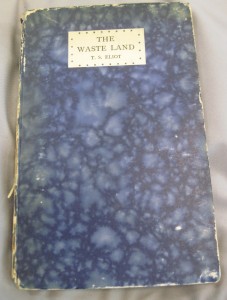

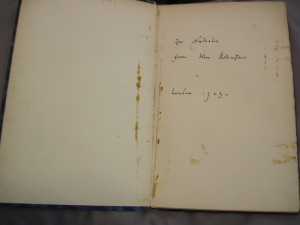

There were personal, creative, and intellectual gifts to be received at the Eliot Summer School. Gifts kept multiplying after the end of School, during the days that I spent in Bloomsbury thinking about Eliot among the things of the present, and reading and researching in the Senate House Library where, in Special Collections, I found a valuable copy of the 1923 Hogarth Press edition of The Waste Land with Eliot’s signature, given by John Rothenstein, once a young Oxford man who had heard Eliot’s fame predicted by Lady Ottoline Morell herself at Garsington, to a certain Nathalie.