Over the winter months, the Institute of English Studies asked our staff and research fellows about their favourite winter reads.

From the classic Dickens to a classic reinterpretation in the form of Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed, we’ve had a fantastic selection of answers that have kept us going during these long winter evenings. Although the cold months are still with us, here’s our answers so far:

Charles Dickens, Bleak House

“Dickens is my master of seasonal conjuring. The first paragraph of Bleak House, published between 1852 and 53, is as evocative of the onset of winter as anything I have ever read:

LONDON. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes — gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers.” – Cynthia Johnston (Lecturer in Book History and Communications)

Dorothy L. Sayers, The Nine Tailors

“The start – a car accident in a dyke in the drear fenlands of Cambridgeshire on a snowy New Year’s Eve. The protagonists – Lord Peter Wimsey (plus manservant) and assorted vicars, young gals, locals, petty criminals. The plot – intricate. The crime – theft of emeralds. The resolution – murder by bells. The book – Dorothy L. Sayers, The Nine Tailors (London: Victor Gollancz, 1934).” – Susan Powell (Visiting Research Fellow) ⠀

Margaret Atwood, Hag-Seed

“I’d recommend Margaret Atwood’s novel Hag-Seed: The Tempest Retold for winter entertainment. Atwood gives a new twist to Shakespeare, reimagining his themes and characters for a performance of The Tempest in a men’s prison in Canada, where magic, monsters, and spirits are now wittily transformed by digital technology. Characteristically, behind the theatrical spectacle Atwood encourages us to think about the value of liberal arts education in prisons and about prisoners’ human rights.” – Coral Howells (Senior Research Fellow)⠀

“One book I’ve recently enjoyed reading was Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed. Time and time again I found myself laughing out loud. I hadn’t thought something she’d written could be so funny and cheering. The sheer cleverness of plotting was a delight” – Jane Roberts (Senior Research Fellow)⠀

Charles Dickens, The Signalman

“Winter is the season for ghost stories, so I’d choose Dickens’ dark, unsettling The Signalman, or one of M.R. James’ even more disquieting tales. Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, first published in 1977 but now enjoying a renaissance, is a lyrical, very personal account of the Cairngorms throughout the year, but her chapter on ‘Frost and Snow is especially evocative of the endlessly changing winter conditions in Scotland’s mountains.” – Alan McNee (Postdoctoral Visiting Research Fellows) ⠀

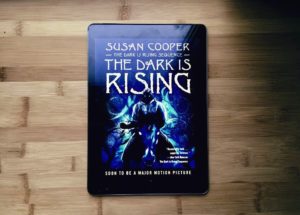

Susan Cooper, The Dark is Rising

“Every winter I turn to Susan Cooper’s ice-cold children’s fantasy, The Dark is Rising for its heady combination of snowy magic and icy menace. Set between the Winter Solstice and Twelfth Night, it is a novel about change, transition, and growing up, poised between the safe warm spaces of childhood and a snow-filled landscape, full of unknown dangers, but full too of magical possibility.” – Susan Cahill (Visiting Research Fellow)⠀