This blog post by Dr Karen Attar is part of the The London Rare Books School which took place 18 June-6 July. The annual summer school consists of a series of five-day, intensive courses on a variety of book-related subjects taught in and around Senate House, University of London. [Photo credit: @TamaraBelts]

What does a medieval book of hours have in common with Lady Chatterley’s Lover? The obvious answers: both have been banned, and both have been best-sellers. A less obvious answer: students from across the world pored over both during the London Rare Books School of June and July 2018. They traced the difference between the first, lavish, expensive privately published version and the cheap Penguin edition of Lady Chatterley and learned how an illuminated fifteenth-century book of hours, exquisite as it seemed to the inexperienced eye, was clearly provincial and aimed at a customer with a moderate income, the quality of the illustration proving it to be “the Primark version of haute couture”.

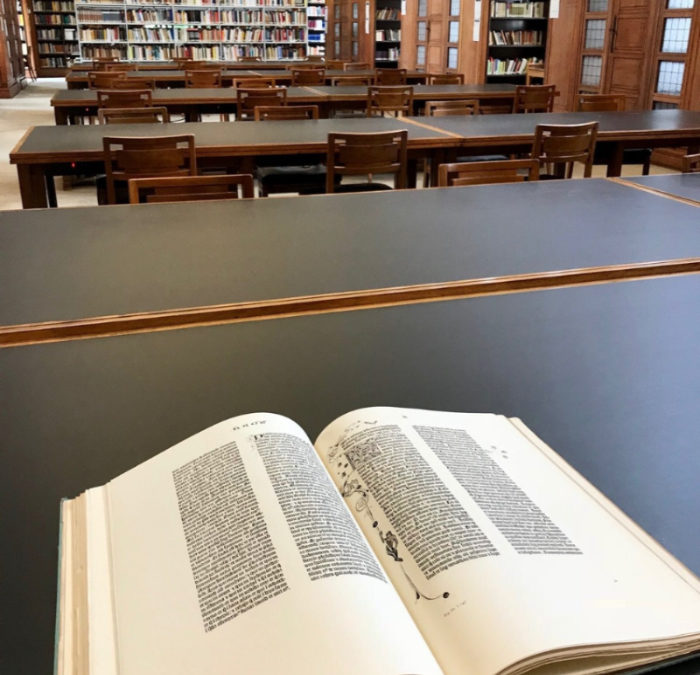

The London Rare Books School is always an exciting time for Senate House Library, as a range of its holdings contribute to the teaching and learning process. Since the School began twelve years ago, the Library has been contributing material to enhance courses, from examples of different historical binding techniques to books demonstrating the diversity of English publishing in the seventeenth century. In 2018 it serviced several new courses. Seldom-used collections were mined extensively: the Littleton collection of landmarks of early music printing, for a course on Early Music Printing and Publishing, and the Craig collection of twentieth-century books on sexual customs and practices for a course on forbidden books. Better-known collections were used in a new way, as, for example, students on the course on the history of paper bent over the endpapers of Kelmscott Press books looking for watermarks. Some highlights:

The Book in the Ancient World has been running for several years with the use of a facsimile of an ancient manuscript from the Library’s palaeography collection and a fragment of papyrus. This year for the first time it included Renaissance printed reception of ancient texts. Various teaching sessions have pointed out the use of abbreviations in Latin incunabula; here the students saw such abbreviation first-hand also for Greek. A volume which aroused considerable interest was an edition of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War from about 1483 (ISTC it00359000), thought to have been owned at one time by the celebrated eighteenth-century classical scholar Richard Porson (1759-1808). Extensive marginal notes have been washed to leave faint traces of their former selves. Unsightly black smudges in the margins demonstrate the unfortunate attempt by a different chemical method to bleach out uglifying manuscript notes.

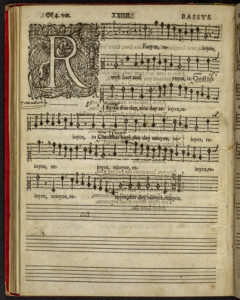

Annotation arose in a different form in the context of music publishing. William Byrd’s Songs of Sundrie Natures (1589) is a rare book: the Senate House Library copy is one of just five in Great Britain recorded on the ESTC, and one of nine worldwide. Manuscript intervention renders it particularly interesting. Two staves have been added by hand on one page, and a printed correction has been pasted down on another. Both of these changes probably stem from the print shop. What most certainly would not have originated in the print shop is textual emendation. Whereas the Christmas hymn invokes its audience: ‘Rejoyce, rejoyce, with hart and voice, in Christ his byrth this day’, somebody in November 1605 or later has changed this to a call to rejoice in ‘our escape’ [from the Gunpowder Plot] this day.

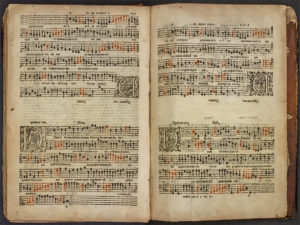

Another curiosity arose as students looked at Thomas Morley’s classic treatise A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Mvsicke (1608). Most of this is printed in black type, but one opening towards the end of the book shows the musical notes in a mixture of black and red. Why the red? Discussion was in order with the tutor of another LRBS course, Colour Printing 1400-1800.

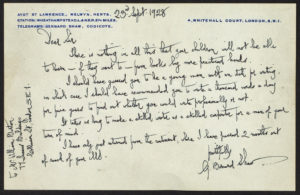

And so to the twentieth century. In Digital Scholarly Editing, students learned to edit texts online, reading letters and literary manuscripts from Senate House Library to note features to convey. Among them was a caustic letter from George Bernard Shaw to an aspiring, unpractised writer who had had the temerity to send Shaw a manuscript: “It takes as long to make a skilled writer as it does to make a skilled carpenter for a man of your turn of mind”. In the LRBS context, the main curiosity was not the main message Shaw conveyed to the man, but Shaw’s explanation for a delay in replying to him: “I have only just returned from the continent, where I have passed 2 months out of reach of your MS”. Supposing one could not decipher Shaw’s writing of ‘MS’, how would one present it? And assuming that one could, how would one expand the abbreviation, if so desired, in a digital edition?

Witnessing the fascination with texts from all sorts of perspectives, noting links as the subject of one course is reflected in another, hearing and participating in discussions about books, encouraging tutors to come back and delve further into elements of Senate House Library’s special collections: such activities are not only at the heart of the University’s mission, but are a sheer joy.