This guest post was written by Patricia Lovett, a tutor on the Palaeography Summer School (10-14 June 2019).The London International Palaeography Summer School is a series of intensive courses in Palaeography and Manuscript Studies. Courses range from a half to two days duration and are given by experts in their respective fields from a wide range of institutions.

The recent hugely successful Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition at the British Library included not just the opportunity to see for the first time in one room manuscripts such as the Codex Amiatinus, the Book of Kells and the Utrecht and Harley Psalters, but it was also a showcase for the skills of craftspeople of the time – from vellum and parchment preparation, gold beating, pigment production, the techniques and artistry of the scribe and illuminator and, in the case of the tiny St Cuthbert Gospel, the book binder.

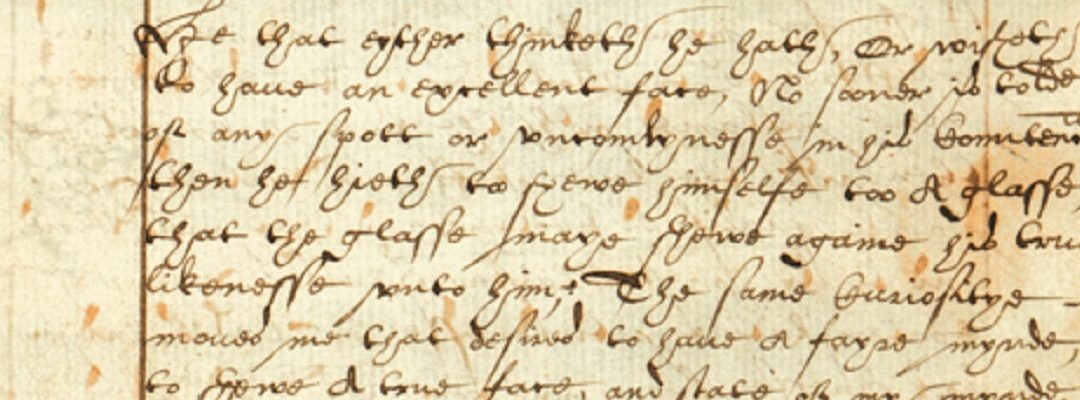

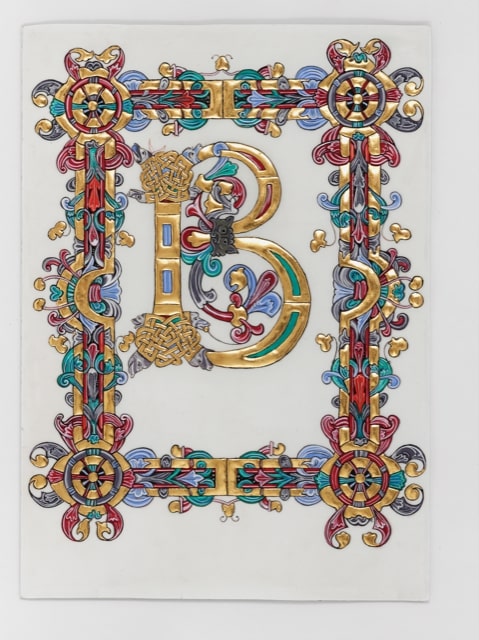

I stood amazed in front of the Codex Amiatinus for many reasons, one being that it was a manuscript that for years I had longed to see and never thought I would, but also because I looked at the sheer size of it and wondered how on earth they managed to bind it! I also had a particular interest in the Eadui Psalter, also in the exhibition, as I copied the Beatus page as it was the one used for a series of short films demonstrating how manuscripts were made both for the exhibition itself and for the joint British Library and Bibliotèque nationale’s Polonsky project online website.

Addressing these particular heritage craft skills in the twenty-first century does not make for comfortable reading. There are now no full-time book binding courses in the UK, so when this generation of book binders hang up their nipping presses and finishing tools there won’t be anyone who has sufficient high-level skills to rebind books for similar exhibitions. There is now only one single parchment and vellum master craftsman left in the UK. No gold is now beaten here, it is all imported, and this is a craft skill that has been in this country since before Roman times. And there are no full-time calligraphy and illumination courses similar to the one where I learned the skills some years ago.

Of course, there will always be those who self-fund to go on courses such as the ones I ran associated with the British Library exhibition, and the 3-day course I run each year on the traditional skills of the mediæval illuminator, but these are simply taster courses – barely sufficient for anyone who wants to practice this aspect of manuscript production at a high level and professionally.

These are just some of the concerns of the Heritage Crafts Association which is launching the second iteration of the Red List of Endangered Crafts next month, whereby crafts that have been carried out in the UK for at least two generations (so not just UK crafts) are put into one of four categories from extinct to currently viable. There were 17 critically endangered crafts in 2016, with only one or two practitioners, and it’s likely that this number will increase.

It is also rather frustrating when there is government funding for contemporary and design-led crafts through the Crafts Council, but no central support whatsoever for heritage crafts skills, nor the crafts that have been practised in this country for centuries.

However, the picture isn’t completely gloomy. Last year the Heritage Crafts Association set up the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Craft which seeks to get those organisations with an interest in craft to work together to make change – and right in the heart of government.

We are also launching an Endangered Craft Fund in March to support those working in the crafts in this category of the Red List of Endangered Crafts such as wanting to learn or improve skills, buy tools and materials or even re-furbish old machinery – the presses at Two Rivers paper in the West Country, for example, are from the nineteenth century!

And in the ten years since we were set up we have managed to get National Honours for sixteen of our world-class craftspeople now recognised here in their home country (they often are more prominent abroad where their craft skills are admired and are in demand); this is a 100% success rate.

The Association also set up and run the Heritage Crafts Awards, whereby a trainer, volunteer, maker and a craftsperson making in Britain are awarded a significant sum, as well as a maker in endangered crafts.

However, without that central support we struggle to do all that we need to and rely on our members to back our activities, supplemented by funders. So this is an unashamed plea to you to become a member. If you, too, are concerned about our heritage craft skills continuing into the future, including all those crafts that contributed to our wonderful manuscript heritage, please do join us. It’s only £20 a year (6-7 cups of coffee in London?) and every single member really does make a difference and helps us to do even more. Visit heritagecrafts.org.uk for more information.

Patricia Lovett MBE

Scribe and Illuminator

Chair, Heritage Crafts Association

The Beatus initial from the Eadui Psalter copied by Patricia Lovett MBE (© 2018 Patricia Lovett)

Patricia working on the Beatus initial