Gillian Neale, M.A. in the History of the Book (IES).

This year’s London Rare Book School (17 June-5 July) comprised eighteen short but intensive book historical courses which explored various aspects of the materiality of books and their makers, users and editors from Celtic times to the present day. Among the keenest pleasures of these courses for the students are the handling sessions, many of them held in Senate House Library, during which they examine books, manuscripts, letters, ephemera and other materials drawn from the Library’s diverse and extensive Special Collections. Materials are intended to support, illustrate and even extend beyond what is taught in classroom seminars. As both an invigilator and student for the duration of London Rare Book School, I was perfectly placed to witness the value-added that handling rare – and less uncommon but nevertheless important – books and manuscripts can bring to the learning process, as well as to gain a greater appreciation of the depth and diversity of the collections housed within the library and what a rich resource they represent for any researcher.

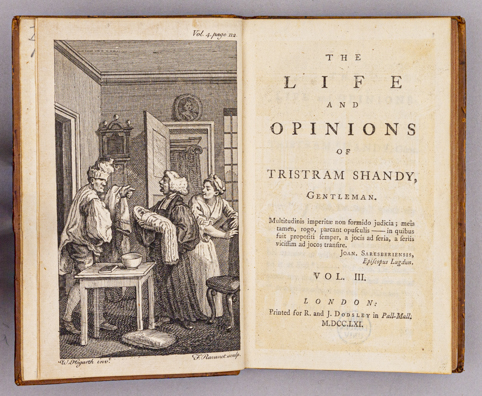

It was hardly surprising that handling sessions for The Publishing History of the Novel and The Woman Reader courses included first editions of titles by authors such as Scott, Dickens, Richardson, Eliot, Sterne, Austen and the Brontës. Leaving aside the question of literary value, the physical copies of what have become canonical works were studied in the context of the publishing conditions and reading audiences of their times. Close examination of the nine small and seemingly uniform volumes of Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1760-1767) belied the fact that they comprised a made-up set with imprints from three different printers. Internal evidence showed different owners for the various volumes, some of which were differentiated by manuscript notes, others by the author’s signature, which led to some brief discussion about binding styles, provenance and marginalia – topics which were covered in-depth in the courses on Provenance and Bookbinding, but which engaged student interest in every course I invigilated. By contrast, the three volumes of Scott’s Kenilworth (1821) were sufficiently weighty and handsome to signify the author’s reputation, as well as to substantiate the novel’s claim to raising both the profile and the price of the three-decker format, and sparked discussion about celebrity authorship, circulating libraries and reading spaces.

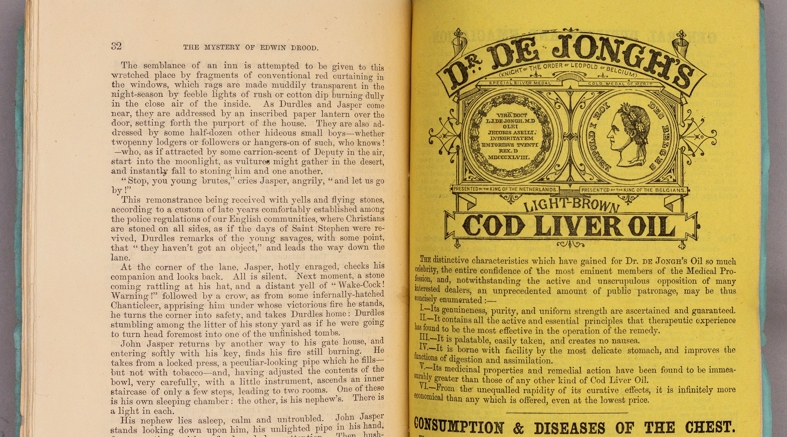

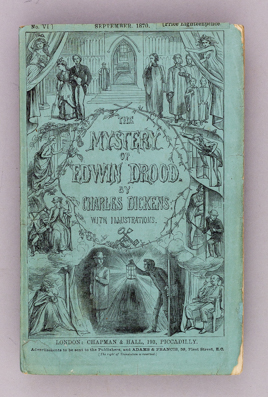

Victorianists were understandably thrilled by The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) in its original monthly part-issue format, and immediately engaged with the forty or so pages of paratextual content preceding each instalment – mostly advertisements for the latest fashions, furnishings and foodstuffs, all of which was discarded in the binding process. The publisher’s rather commercial reaction to Dickens’s death was wryly noted: a price label for eighteen pence pasted over the printed cost of one shilling on the sixth and unintentionally final part – no mean inflation of profits on a circulation in excess of 100,000 copies.

Yet historically important books have a way of transcending their specific periods or genres and making connections that both reach forward and look back in time. When Edwin Drood featured in a handling session for the Digital Scholarly Editing course, the same paratextual material presented a different set of challenges. Students were asked to consider whether it was extraneous to the text and should be accordingly disregarded, or whether there might be a case for including any part of it and, if so, how best to capture that information? Interestingly, most of the group came down on the side of not incorporating such material since it appeared to bear little relevance to the text, irrespective of its interest to either contemporary or modern readers, and thereby partially redeeming Victorian binding practices. The final observation on these advertisements came from a student whose subject is medieval and early modern medical history. Immune to the delights of Dickens as an author, her attention was caught by the number of quack remedies and patent potions promising all manner of spurious benefits, and how extraordinarily similar some of them were to early modern ‘cures’. Plus ca change.

The Blocks and Plates course incorporated hands-on sessions across London at the British Museum, the British Library and the St. Bride Foundation, as well as Senate House Library, where Victorian woodblocks were on display, including an example of a large boxwood block, rare because of its size, and some uncut woodblocks showing the fine pencil and chalk drawings made as guides for the cutting. To give some insight into the piecemeal nature of a cutter’s work, a full-page illustration from the Illustrated London News (1842-2003) was copied and cut into parts corresponding with the original woodblocks. Students were asked to guess the subject of the whole picture from a single part, which was more challenging than expected. But the exercise proved a point; that production of woodblock illustrations for publications such as the weekly Illustrated London News was a wholesale commercial operation rather than a romantically artistic one.

Using Publishers’ Archives, a new course for 2019, gave students the opportunity to dip into the archives of Gerald Duckworth and Co (MS959), the publishing house set up in 1898. Early authors included D.H. Lawrence and Evelyn Waugh, but in our case we enjoyed an orderly romp through the author correspondence files for more modern authors, including Beryl Bainbridge and Penelope Fitzgerald. Some of these contained much ephemeral material – for example, art postcards with charmingly personal messages in the case of Fitzgerald. We also examined correspondence concerned with selling overseas rights to Bainbridge’s works and the challenges this threw up for the firm, particularly in pre-EU days. But the Duckworth archives, while accessible for genuine research purposes, remain privileged so no photographs here. Which leads me to conclude by hoping that this necessarily short and focussed survey of a very few of Senate House Library’s Special Collections will tempt bibliophiles, academic or otherwise, to explore them, and perhaps register for one of the LRBS courses.

Registration for LRBS 2020 will open in the Autumn. Click here to sign up for our newsletter and be notified when registration opens.

With thanks to Senate House Library Archives.