I wonder how many millennials right now are relistening to the inimitable Stephen Fry recordings of the Harry Potter series? I know of at least half a dozen. For many of my friends those audiobooks are synonymous with comfort; the literary equivalent of making yourself a mug of hot Ribena; or carrying your duvet to the sofa, settling down, and putting on a film you have seen so many times you can recite along with it (in my case, this is the Lord of the Rings films or any number of Disney movies). It’s what you did when you were younger, when you were ill or heartbroken or you couldn’t sleep. For many of us now those conditions – illness, insomnia, heartache – are frequent. So, to calm our minds and rock our hearts, we are turning to our comfort foods, our comfort films, and our comfort books.

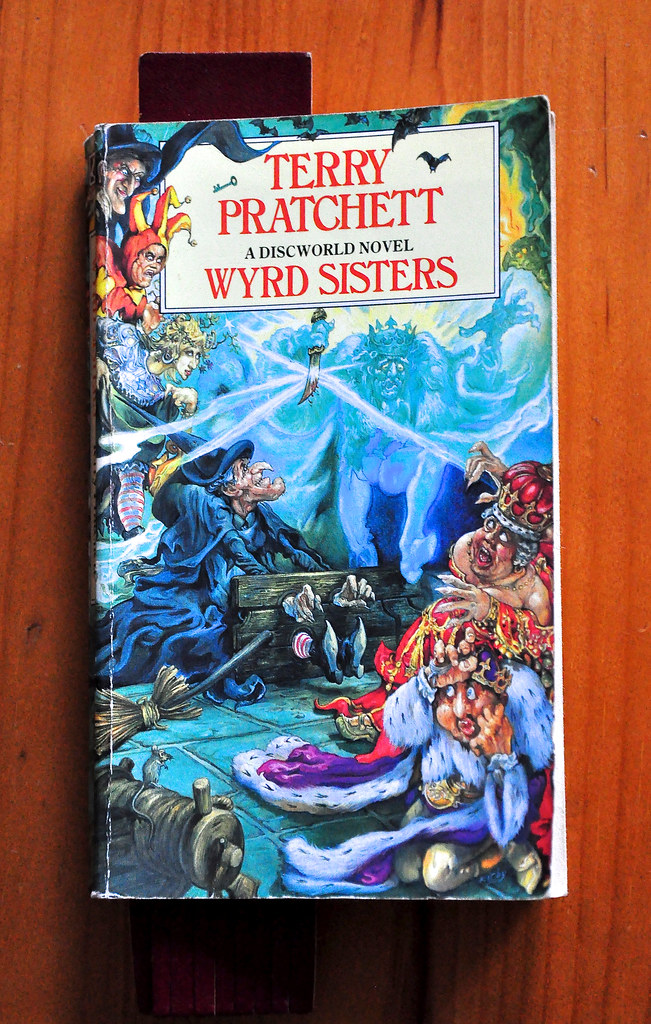

Despite being a huge Harry Potter fan, neither the books nor the recordings are my go-to comfort books. Instead, when I need to be soothed and distracted, I reach for a Terry Pratchett Discworld novel. I love them. For starters, their sheer readability: the original editions, with the Josh Kirby illustrations, are a joy to hold. They are small (10.7 x 2.5 x 17.8 cm), the perfect size to hold in one hand while you cradle a mug of tea in the other. I love the fact that they don’t have chapters, merely scene breaks. This makes them both utterly undemanding – there’s no sense that you need to reach the end of a ‘chapter’ before you can take a break – and utterly binge-able – you don’t need to put them down at the end of a chapter, and can keep going without any guilt that you haven’t moved for hours.

Their comfort also comes from the fact that they are a brilliant escape. Like the Harry Potter series, or Lord of the Rings, they create a vast fantasy world. Unlike these series, however, they don’t focus on an individual, or central group of characters. There are recurring figures, absolutely, and mini-series within the overall Discworld series, as well as stand-alone characters and narratives which don’t really recur. This makes the whole series so customisable for the individual. My two favourite mini-series within the Discworld novels, for example, are those which focus on the Ramtop witches and the Ankh-Morpork policeman Sam Vimes. Personally I find the books which focus on the wizard Rincewind slightly tedious, and that’s absolutely fine because you don’t need to read them to enjoy the rest of the books.

The fantasy world that Pratchett creates in these novels is both an escape and also a return to the familiar. Pratchett’s literary influences are wide-ranging and criminally underexplored, but his Discworld stories frequently retell well-known narratives. The witches novels, for example, often replay Shakespearean plots. There’s a certain satisfaction to be gained in realising that Lords and Ladies retells A Midsummer Night’s Dream (and really delves into what is so wrong about elves treating humans as playthings), or that Wyrd Sisters jumbles together Hamlet and Macbeth to explore what it means when you try and steal a kingdom for love of power, not love of the land.

During lockdown it is the witches Discworld novels that I have found myself returning to. Unlike the City Watch/Sam Vimes novels, which are fundamentally ‘whodunit’ detective fiction, the witches books are about when communities are under threat, and the choices that individuals have to make in these situations. These narratives revolve around individuals who must hold themselves apart from a community in order to save it, and they contain a clear morality which is both beautifully nuanced and utterly absolute in its dichotomy of good and evil. The witches – and most especially the central witch, Granny Weatherwax – are those who occupy a liminal position, poised between right and wrong, light and dark. And they are those who always must make a choice between these absolutes, so that their community does not have to. Right now, escaping to an alternative world that is nevertheless familiar, where matriarchs protect their communities by making the impossible choices so others don’t have to, is hot Ribena for a troubled soul. This, to me, seems to be the definition of comfort: something that is simultaneously an escape and a return. Pratchett, as ever, has the pithiest lines to convey such as thought: ‘They thought they wanted to be taken out of themselves, and every art humans invented took them further in’ (Wyrd Sisters).

Eleanor Hardy is the Events Officer at the Institute of English Studies. She recently completed a PhD on imitation in early modern poetry.

Full agreement with you! Comfort and fun are delivered every time along with piercing insight into many of the challenging aspects of our world eg. Sam Vimes’ championing of the goblins in the later narratives and Tiffany Aching’s attempts to resolve abusive behaviour in her community.

I too have returned to the Sam Vimes books, he is my favourite character. I might have a slight crush.

I own every Discworld book and read them again and again. While I have a firm favourite in the watch books, Granny and her Ilk are not far behind. I still think it a pity that Polly Perks only got one book, but this makes it even more a treasure to re-read. As an avid tabletop rolr-player O often infuse some of sir Terry:s xit and wisdom onto my characters and this has yet to fail me.

I’ve gone to the Discworld almost constantly in audiobook since I got covid 12 months ago and have never recovered. They’ve distracted and at times made me laugh out loud. I was late to take to Pratchett but he’s been a wonderful companion over the past year.

I have spent much of the pandemic listening to every Discworld audiobook I could get my hands on. There are some not available in the US. It helps me relax.

I could not agree more. The Discworld books, along with Nation, are the books I go back to time and again. They still make me laugh out loud after dozens of re-readings, but what makes them stand out is the sheer humanity of them. Humans and trolls and dwarves and orcs and goblins and even vampires are all just people, doing what people do. Pratchett had his head screwed on right and his heart in the right place, even without the services of a really skilled Igor.

GNU Sir Terry. Mind how you go.

Discworld is where I like to go (in my head) when the real world is too worrying for me and I need to feel that someone sensible is in charge. Terry Pratchett is like Monty Python with a story line that just goes on and on, funny and fascinating with characters who behave like real people even while doing impossible things like magic. It’s satire and suspense, folklore and pop culture, and if the heroes are too good to be true, that’s OK because they are kind of dim at times as well, and they are dealing with Things From The Dungeon Dimensions and some rather realistic villains.

Ditto. I too have turned to Pratchett, rereading in publish order