We had just started our annual History of Books and Reading seminar series on the theme of ‘Reading and Wellbeing’ when the COVID-19 pandemic broke. In the space of two months, lives have been turned upside down and our most natural instincts suppressed. Pandemic social distancing rules have cut us off from participatory culture, sport and social life, and is causing a surging mental health crisis. Never has reading matter, specifically, having books at home, been of greater importance. Confined to our homes, many have turned to the printed books on our shelves and the eBooks on our digital devices for reassurance, reflection, or escape. Putting this seminar series together in the pre-Coronavirus world, we had never imagined that our research topic would be so close to home for so many people, including ourselves.

Despite the surge in digital cultural consumption via Netflix, which has added 16 million new subscribers in the first three months of 2020, reading has held its own during this global lockdown. Some reading during the pandemic has been predictably immersive: readers have looked to earlier accounts of quarantine to make sense of an inherently disorientating experience. Sales of pestilence classics like Albert Camus’ La Peste (1947) and Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) are at an all-time high, with Marcel Theroux commenting that the books had ‘gone the way of dried pasta and toilet roll’, despite the fact that the latter is out of copyright and free online. Both are currently virtual book club and reading group favourites, with Camus being promoted by the French Embassy’s Albertine Club, Seattle’s The Stranger (which runs a ‘silent reading party’ quarantine club), and the YouTube Vlogger ‘Better than Food’ (over 31,000 views since 17 April), while Defoe’s factual-fictional ‘novel’ has been picked by The Guardian (reading group choice for May), the Silent Book Club, and even by the futurist, Bryan Alexander. What this clearly demonstrates is our inherent need (as humans and readers) for shared, collective experiences, mediated via text, to make sense of extreme upheaval.

But not all reading during times of mental anguish or physical danger is immersive; indeed, the contrary impulse, to escape into something altogether more secure and predictable, is a much more common response. Writing in The Guardian, Josephine Tovey in ‘sense and social distancing’ has commented on how the pandemic lockdown has given her ‘a newfound affinity with Jane Austen’s heroines’, their lives shaped by ‘domestic confinement and social inhibition’. Like Miss Bingley’s exhortation to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, we are all now confined to our homes and encouraged to ‘take a turn about the room’ to refresh ourselves, but what this account of re-reading a classic novel reminds us is that returning to an old and familiar favourite book can have a particularly strong restorative power. As evidence from the UK Reading Experience Database demonstrates, readers have been finding solace – both comfort and escape – by reading the novels of Jane Austen for more than two centuries.

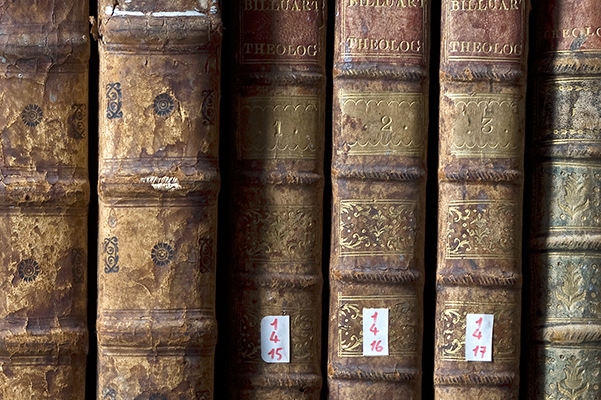

Reading a book in a time of upheaval can contribute to our mental wellbeing through positive emotional affect, but even being in the company of our own books can be reassuring and rewarding. Despite our increasingly (almost exhaustively) online lives, the material book is now firmly back in focus, and not just as a backdrop to endless Zoom meetings – although even on that score, the wittily parodic and highly insightful Bookcase Credibility Twitter account, which has amassed over 35,000 followers in under a month, has given a new lease of life to social media ‘shelfies’. In our quarantine confined, digitally mediated existence, we literally are what we read, and our cultural capital is now is on display to the whole world, in material form. As Amanda Hess has noted in The New York Times, the credibility bookcase is the ‘quarantine’s hottest accessory’, and one that cannot be counterfeited with Ebooks. In the semiotics of the pandemic, the well-curated bookcase has become a manifestation of our mental state, and perhaps for the first time during this barber-less interlude in human history, our books are more important than our hair. And yet, as John Quiggan points out, this newly respectable flaunting of cultural capital can entrench existing socio-economic inequalities; the personal library has always been an overt display of wealth as well as knowledge.

As much of the research from contributors to our ‘Reading and Wellbeing’ seminar series demonstrates, reading material books, especially in a shared context, has an appreciable psychological, emotional, and moral value. On 23 April 2020, for the only time in British history, the collective shared reading celebration of World Book Night and #Reading Hour (7-8pm) was followed immediately by the five minute national clap for NHS workers and carers. Two collaborative, successive shared experiences, yoking together reading and wellbeing, because at the end of the day, they are inseparable.

Shafquat Towheed, The Open University