One morning in May, 1741, outside a small farmhouse in the village of Hayton in Kent, the 20 year-old Elizabeth Robinson (1720-1800) cried as her father, Matthew Robinson, refused to embrace her. He feared transferring the smallpox which had already infected Elizabeth’s sister Sarah (1723-1795), who was permanently scarred by the disease. Elizabeth described the scene to her friend Margaret Cavendish Bentinck:

I have not seen my Pappa nearer than some hundred yards, for he does not think it worth while to put on another Coat and will not come near me in that he has worn in the House with my sister; tho he had never been a moment in her Room.

(Robinson to Bentinck, 5 May 1741, Huntington Library, CA, MO 297)

This episode, with its eighteenth-century version of social-distancing, hyper-awareness of contagion, and deep feelings of anxiety and disconnection, resonates with the current situation. The lack of physical affection possible under Coronavirus, as noted by numerous outlets including the BBC and The Conversation, heightens anxiety and adds to feelings of alienation, and Elizabeth’s relationship with her father wouldn’t wholly recover from this perceived betrayal.

The wealthy Robinson family were privileged in their ability to respond to the 1741 smallpox 1741. Then, as now, financial security ensured an easier quarantine experience, with Elizabeth able to stay in the house of a Mr Smith, a tenant of her father’s, when her sister fell ill in April. They were also one of the first generation to benefit from the new practice of inoculation, introduced to Britain from Turkey at the end of the 1720s by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Elizabeth and her brothers would all be inoculated by the end of the year.

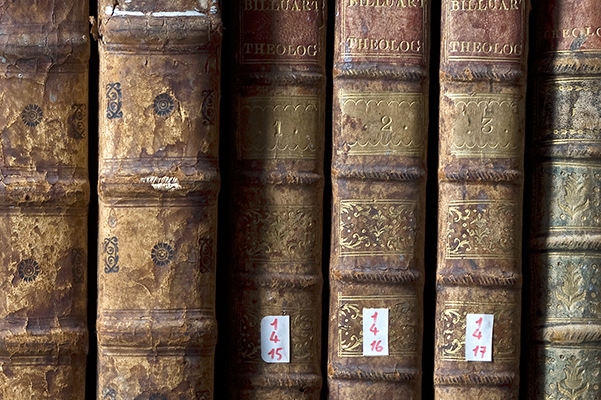

Like many of us today, Robinson filled her lonely hours at the Smith household with books. She read the Lives, a collection of moralistic biographies of ancient Greek and Roman heroes and statesmen by the Greek historian Plutarch and letters between the Roman philosopher Cicero and his friend Atticus. She described them as providing a sense of community in a letter to another friend, Anne Donnellan (1700-1762):

I am forced to go back to former ages for my companions; Cicero, and Plutarch’s heroes are my only company. Pray how do you and Tully [Cicero] agree? I have taken a great fancy to his friend Atticus. I love those virtues which, like the peaceful olive, bloom in the shade; I admire the strength of some understandings, but I love the elegance of his.

(Robinson to Donnellan, 10 April 1741, MO 810)

Not only do Plutarch’s subjects, Cicero, and his friend Atticus become surrogate companions for Robinson, but, like the shared reading through video chat recommended by Ella Berthould in a previous entry on this blog, the books become a communal activity practised remotely with Donnellan. As Robinson would do throughout her reading life, she and Donnellan are reading the same book at the same time, and reporting on their progress in weekly letters. This shared reading not only helped create a sense of virtual community, but it made Robinson’s letters into tools for mutual moral and intellectual progress. Just as she would 50 years and 6,000 letters later, she reads Atticus and Cicero as models of ethical behaviour. On Atticus; ‘I was pleased with him, because he appeared to me just, friendly, charitable, and disinterested,’ (MO 810) and on Cicero, in a later letter to Bentinck; ‘[he] avow[s] every tender sentiment of the heart, open to friendship, and liable to the softest movements of pity’ ((Robinson to Bentinck, 2 August 1741, MO 306). For Robinson, letters and reading become a means for becoming better people, following Cicero and Atticus’ example, embodying Cicero’s own maxim in Laelius, his pamphlet on friendship, that ‘Friendship was given to us by nature as the handmaid of virtue’.

Robinson (later Montagu), Bentinck, and Donnellan later founded ‘Bluestocking Circle’, a collection of highly influential public intellectual women who dedicated themselves to promoting a vision of rational friendship very like shared between Cicero and Atticus, and it started from moments of isolation, alienation, and a need to maintain relationships under highly compromised circumstances.

Jack Orchard is a Research Associate at the Elizabeth Montagu’s Correspondence Online Project at Swansea University, with research focusing on Digital Humanities and 18th century women’s reading and correspondence practices. He is active on Twitter @Jarona_7 and tweets extracts from Elizabeth Robinson Montagu’s correspondence @Montagu_Letters.