Dr Carol Farr, Research Fellow at the Institute of English Studies

A super-star attraction of Trinity College Dublin, the Book of Kells is known to many people across the globe. Besides being a recognisable emblem of Irish culture, it is a complex object. Probably made about AD 800, it contains a lavishly decorated handwritten copy of the four gospels in Latin in an unusually large format. Originally its approximately 370 leaves—now down to 340—may have measured about 370 X 260 mm. Their present varying dimensions of roughly 330 X 255 mm result from at least one episode under a binder’s knife. It has been rebound at least five times, most recently in 1953 into its present four volumes. Its exact place of origin is not known. It certainly was made somewhere in the loosely cohesive culture that ranged from Ireland across Scotland to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, often called ‘Insular’. The monastery founded by Colum Cille (St Columba) in 563 on Iona, off the west coast of Scotland, is a likely place of its making. The book’s modern name results from its medieval location at the monastery of Kells (County Meath, Ireland), founded in the early ninth-century by Columba’s community of monks. Its presence at Kells, however, can be confirmed only from the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, by the documents inscribed in Irish on some of its blank leaves.

Its gospel text is the Latin Vulgate—St Jerome’s translation commissioned by Pope Damasus in the late fourth century—but with many variations typical of early gospel manuscripts from Irish contexts. In many early gospel books, an array of ‘study aids’ accompanies the scriptural text, but the Book of Kells has an extraordinarily extensive series. These additional materials were meant to confirm the gospels’ spiritual truth, as well as to help the reader study them. For example, lists of the Hebrew names from each gospel provide a Latin meaning for each name, intended to help reveal the divine significance of every word. Clarity, however, was not always the priority, exemplified by its flawed canon tables, a set of ten indices which in their correct form would indicate all parallel passages, showing the four gospels’ harmony.

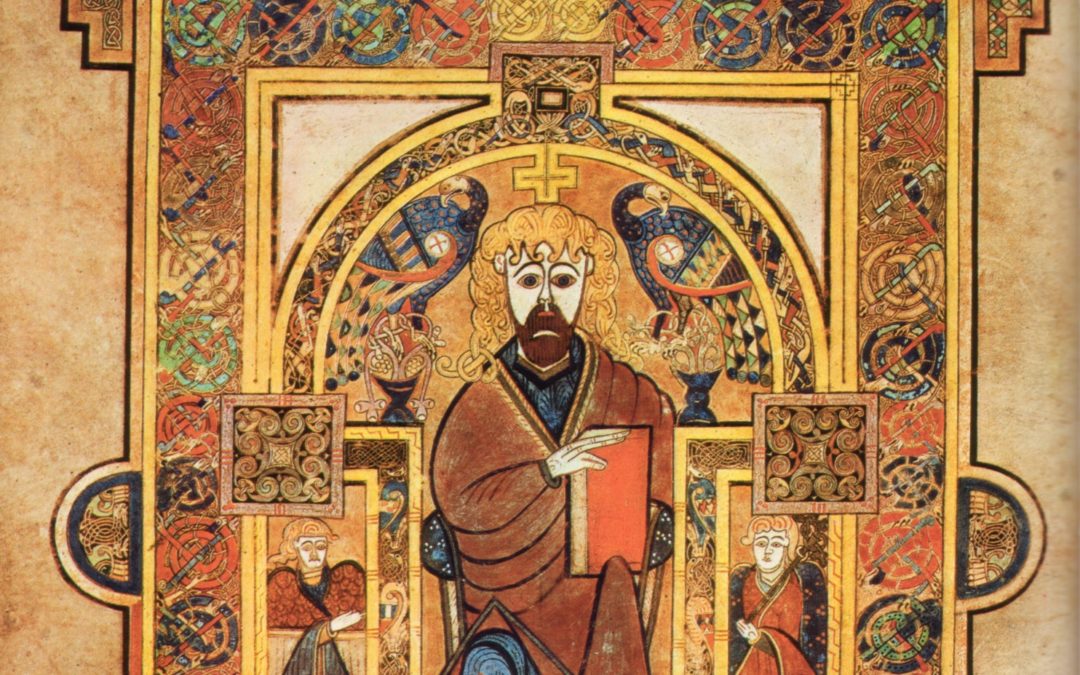

The Book of Kells’ visual art and beautiful scripts underlie its celebrity. It has every type of decoration known from Insular gospel manuscripts. Besides full-page, heavily decorated initials that signal beginnings of important sections of texts, smaller initials often composed of animals and extravagantly contorted human figures articulate minor sections, seeming to respond in various ways to the text’s deeper meanings. Its art looks back to traditions but also has innovative features, such as the two full-page pictures within the texts of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, the earliest surviving intra-textual Latin gospel pictures. Mostly written in the script called ‘Insular majuscule’ or ‘Insular half-uncial’, the number of scribes remains an open question. Whether a single scribe or a team wrote it, it is the product of great skill.

Take a look at the palaeography and manuscript resources on our Palaeography Online page, including more blog posts, a transcription challenge, lectures and recordings.