Dr Karen Attar answers some questions about the use of special collections material from Senate House Library on London Rare Books School courses:

No matter what course they are studying, students on the London Rare Books School benefit from opportunities to work with rare books and manuscripts, along with all kinds of book-related objects, from writing utensils to printing machines. In addition to magnificent libraries around the city – including Lambeth Palace Library, the Victoria & Albert Museum, St Bride Library, and the British Library – Senate House Library (the central library of the University of London), provides material from its special collections to support teaching and learning. We asked Karen Attar, Curator of Rare Books and University Art, for more information on the many kinds of books, manuscripts and objects that have been used on the School’s various courses.

What is the oldest Senate House Library item shown to LRBS students?

Students on the course on ‘The Book in the Ancient World’ are shown fragments of papyrus from Egypt and in Coptic Greek, dated tentatively to the sixth century. These are taken from the Harry Price Archive. Harry Price (1881-1948) collected material pertaining to magic, and one of these fragments contains magical symbols.

Which of the named collections at Senate House Library is used most extensively?

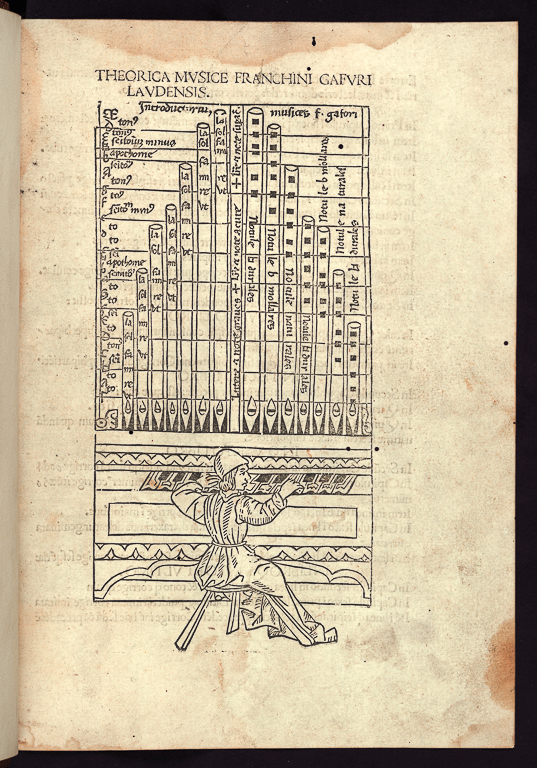

In terms of a single course it would be the Littleton Collection of landmarks in early music printing. Every item in this small collection was used for a course on ‘Music Printing in Europe 1450-1750’ in 2018. The next most intensively used is the Incunabula collection which is drawn on for several courses, e.g. ‘European Bookbinding 1450-1820’ and ‘The Book in the Renaissance’, as well as the dedicated course on ‘Incunabula: Medieval Printed Material.’

Are you asked to provide books or manuscripts from the twenty-first century as well?

Yes. For example, Plantejaments i Objectius d’una Història Universal de la Cartografia = Approaches and Challenges in a Worldwide History of Cartography, edited by David Woodward et al (Barcelona: Institut Cartogràfic de Catalunya, 2001) was used throughout the entire week of the course on ‘Maps and Mapping’ one year. And a facsimile of the Lindisfarne Gospels (Lucerne: Faksimile Verlag, 2003) is used for courses on ‘The Medieval Book’ and ‘The Book in the Celtic World’. These examples reflect the fact that LRBS requires reference materials as well as primary sources. It also shows the continued importance of printed facsimiles.

LRBS runs specialist courses on digital scholarly editing. Are you asked to provide materials for these?

Despite the purely electronic side of the course title, yes, as the practical element of the course relies on having texts to edit. Students have worked with letters by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Robert Southey, and George Bernard Shaw, and literary manuscripts by Thomas Carlyle, Walter Scott, Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Siegfried Sassoon.

Which item in your experience generated the most interactive attention by students?

I think it would be a Kelmscott Press book for a course on the ‘History of Paper’ in 2018, as students pored over the endpaper to discern the watermarks. But other items generate excitement as well: lifting the first edition of the terrifically heavy folio King James Bible to ascertain its function as a pulpit Bible, as opposed to the quarto Geneva Bible for private devotional use; and looking at the 1,809 pictures in the Nuremberg Chronicle to identify duplicates, as a single woodblock does duty for several towns or people. Studying archival material also grabs students’ attention, such as material on obscene literature and its censorship from the Alec Craig Collection (MS1091) viewed on a course on ‘The Forbidden Book’, and correspondence between the publisher Duckworth and its authors (MS959) explored on a course on ‘Using Publishers’ Archives’.

Thinking about different kinds of books, which genre features most in LRBS provision? Senate House Library is particularly rich in its collection of political pamphlets, for example?

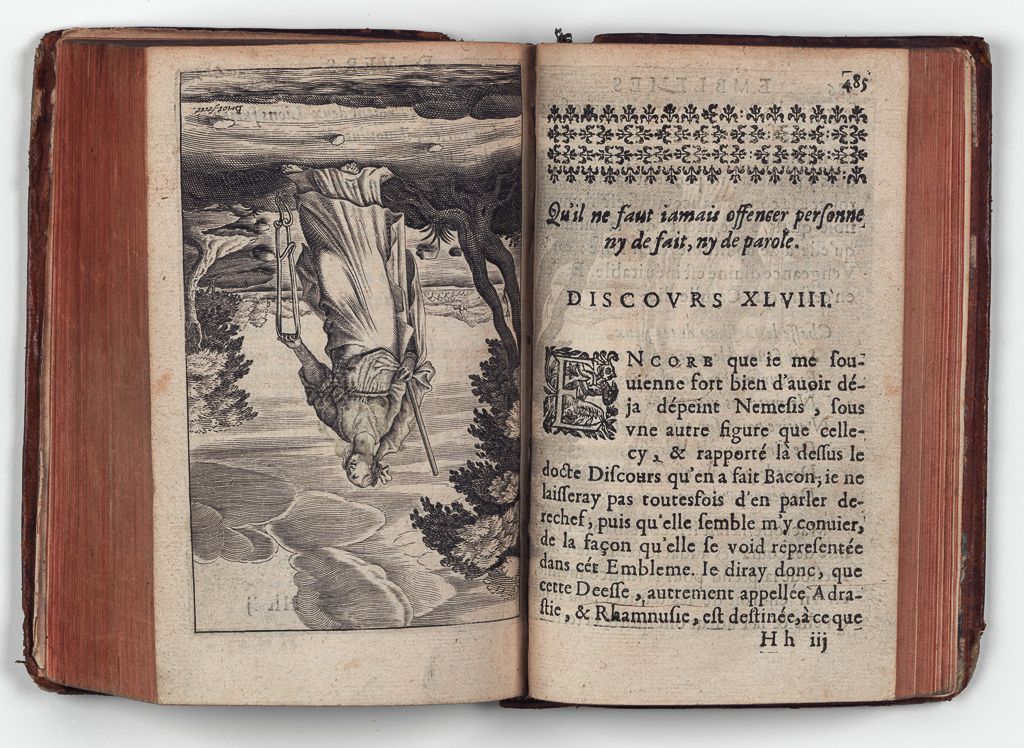

One might expect it to be children’s books as there is an entire LRBS course on this genre, and Senate House Library has two special collections devoted to them as well other specimens scattered across the special collections. But actually it is sixteenth- and seventeenth-century emblem books, used extensively for a session on the course on ‘The History of Book Illustration’. These come from the library of Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence, who collected emblem books to demonstrate Sir Francis Bacon’s alleged input into them to indicate to the initiated his authorship of the works of Shakespeare.

Which LRBS course uses most items?

‘English Bookbinding Styles 1450-1800’. In 2019 Senate House Library supplied 127 books for this course to demonstrate different periods, styles, and materials.

What is the most controversial book to have been brought out for LRBS?

This is for the publishing historian to decide. Three examples: Marquis de Sade’s Histoire de Juliette, ou, Les prospérités du vice and the first privately printed edition of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover have been used on ‘The Forbidden Book’ course. Lady Chatterley’s Lover probably resonates most for the court case against Penguin Books held in 1960 under the Obscene Publications Act 1959. And then Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was for several years a staple of a session on controversial books on the ‘Printed Book in Europe 1455-2000’ course.

The study of rare books is not just about beautiful books in perfect condition. Do tutors ever ask for examples of imperfect books?

Yes, often. Several courses use books with missing spines, including ‘Introduction to Bibliography’ as well as the courses on bookbinding, to investigate book structures. The ‘Provenance’ course makes use of a book from which an ownership inscription on the title page has been cut away to illustrate the challenge faced in provenance research by deliberate expurgation. LRBS has its own teaching collection which contains books with missing pages. These are used on the course on ‘The Printed Book in Europe’ where students pair up to examine books and say what they notice about them.

Which item has excited the greatest individual enthusiasm from a LRBS student? Senate House Library owns two copies of the Shakespeare First Folio, for instance, as well as medieval illuminated manuscripts.

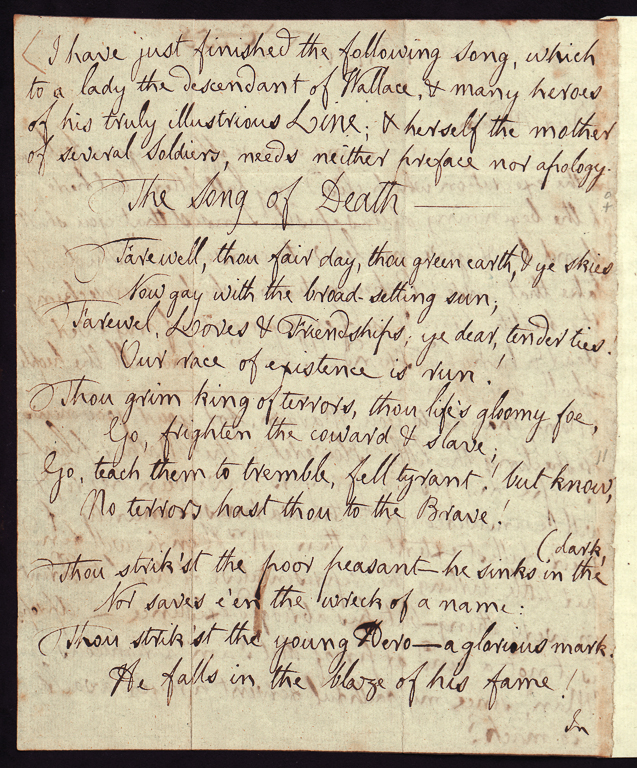

Actually, it was a manuscript letter (SLV/5) from Robert Burns to a long-standing friend, Frances Dunlop (1791).

The fascinating thing about this letter is that it contains a poem ‘The Song of Death’ in the middle of it. The letter might conceivably have been used on the ‘History of the Book in Scotland’ course where students had the opportunity to compare the first and second editions of Burns’s Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, published in Kilmarnock and Edinburgh respectively. But in fact the letter featured on the ‘Introduction to Digital Scholarly Editing’ course where it thrilled a librarian employed at a Burns collection.

What request posed the greatest challenge to provide?

The hardest example – and consequently the greatest triumph – to pinpoint was an eighteenth-century book owned by a woman, which was requested last year for a course on ‘The Woman Reader’. A frequent challenge when providing books for LRBS is that tutors are more interested in particular elements of book production or post-production history than in the identification by author, title, or subject that is best provided by the traditional catalogue. If a request is for a book published by a syndicate (wanted for the course on ‘the Printed Book in Europe’) or a washed book for ‘Provenance’, I can satisfy it by judicious keyword searching. That is harder for something like “a book owned by a woman” because provenance notes, while they name known former owners, do not state their gender. I located an edition of Hannah More’s Sacred Dramas (1782) by doing a catalogue search on the phrase “her book*” and limiting it by date.

Finally, what item or course has had the most effect in inspiring further research?

We wait to see. If you are reading this as a former LRBS student or tutor and have undertaken further research or published an article based on or using your experience of materials seen at LRBS, please let us know!

Dr Karen Attar is Curator of Rare Books and University Art at Senate House Library, and a Research Fellow in the Institute of English Studies.

To find out more about some of the courses mentioned in this interview, see https://www.ies.sas.ac.uk/study-training/study-weeks/london-rare-books-school/course-descriptions