Connor, 11, is a hopeful entrant to BBC Radio’s short story writers’ competition 500 Words 2020. I heard him interviewed just the other day. Reading a good book, he said, can ‘take you to another place’. That’s why he was entering the competition. Connor wanted to use his words to transform his readers’ sense of their world, to take them somewhere different. It’s hard to imagine a time when this example of an 11-year-old’s wisdom would resonate more strongly in those listening.

Personally prone to the doomscrolling of the previous blog in this series, and aware of the research hiatus trailed in its launch, in this post I take up Connor’s invitation to use words to travel to another place.

The huge amount of print and digital content on this subject proves how many others are travelling too. Some want plague fiction. Camus’s The Plague (La Peste; 1947) and Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) are selling at record levels. Some seek broader-category dystopias while others have identified instead ‘joyful books for dark lonely times’.

One friend is hedging his bets, combining binge reading of Tony Hillerman novels with regular forays into Marcus Aurelius. Some normally avid readers will have temporarily lost their faith in books altogether.

I don’t want dystopia. I choose to set a course away from bluster, bravado, ‘post-truth’, cheats and oppression. But, because I’m on route to what I want to be a real place, I can’t call it utopia either. To help me travel, and in the hope that they will speak more widely also given the extent of the mess we are in, I recruit two women writers: one of novels, one of essays; one American, one British; one contemporary, one who struck publishing gold in 1888; one whom I was reading in a library (in a library!) just before lockdown, and another I’ve been reading lots more of since lockdown began.

Mary (Mrs Humphry) Ward is not read much these days. An influential ‘anti’ of the pre-1914 era, she’s known mainly as a lobbyist on the wrong side of history. I see her rather differently now. My recent experience of reading Robert Elsmere, her triple-decker bestseller, was closer to my joyous undergraduate discovery of Middlemarch than almost anything has been since. A broad, wise analysis of the religion and politics of a changing society, as well as a moving love story, I choose her words to travel with, more precisely, because of her social advocacy. Ward’s hero, in his growth and development, embraces the ‘potent spirit of social help’. He founds and leads a settlement in London, at the vital heart of which are the practice of storytelling, and a library. Both are shown by Ward to promote the empathy of the settlement project. If I had to choose one demonstrated behaviour we need more of right now, this would be it.

I also choose Rebecca Solnit’s words, in her campaigning book of essays, Recollections of My Non-Existence (2020), to take me to another place. Solnit writes on a small white desk. Her twenty books, as well as innumerable reviews and essays, letters and emails, have been crafted on the same piece of furniture, what she calls a platform for her voice. The desk was given to her by a friend who was stabbed multiple times by an ex-boyfriend who didn’t want her to leave him. Solnit wonders if everything that she has written since has ‘literally arisen’ from that experience of witnessing an attempt at silencing a woman, and the gift that resulted. Her words are designed to strike at the heart of oppression by ending voicelessness, one experience at a time.

These writers understand the life-limiting effects of poverty, and the violence done and endured as one catastrophic result. I choose them for this keen-eyed, caring observation, and because they simultaneously appreciate the basic connectedness between members of this human race. With their words, these women build not just a place to travel to, but a place for living in.

Sara Haslam (The Open University/English & Creative Writing)

I read Rebecca Solnit’s ‘The Faraway Nearby’ (Granta 2013) at the beginning of confinement in rural France, where every small detail of the immediate environment suddenly became magnified and important. Her title now in the light of your commentsite now seems very apposite. Her small linked essays were wonderfully soothing before sleep.

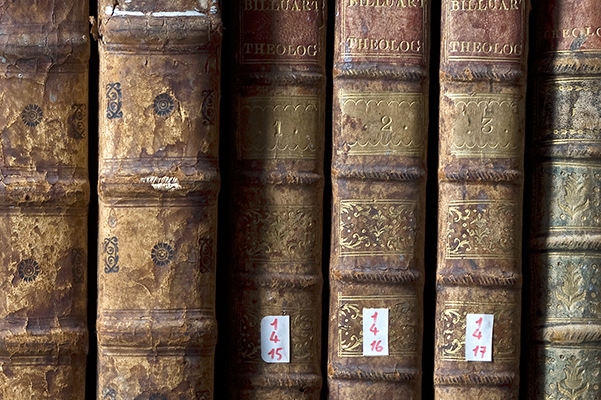

Having read your blog, Sara, and dipping back into my copy of Solnit’s The Faraway Nearby, I came across this sentence: ‘Books are solitudes in which we meet’. This image, and the thought of reading as travelling, resonate so strongly right now.

Thank you, Helen and Isabelle, for great comments, and for continuing the conversation!

In the feedback I’ve seen so far, The Faraway Nearby has proved a very popular Solnit text right now. I think perhaps the reasons are alluded to in both your posts – her extraordinary treatment of the environment, from ripe apricots to ice, at a time when we too can/must focus on what is under our noses. And her attention to books and stories throughout as places where we can, meet, yes, when we are removed from people and places we love and for who knows how long. It turns out we meet in books of essays as well as Narnia 🙂