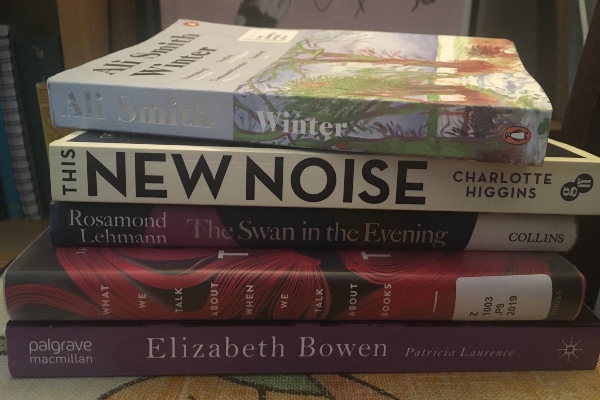

Here is this week’s pile of books. No doubt they will last longer than a week – as Susan Elderkin noted in her blog, it is not easy to read in a pandemic. When I was completing my doctoral research around full-time work, I used to have a daydream of being sent to prison. My version of incarceration bore scant relation to reality and simply involved peace, quiet, an unlimited supply of books, something to write with, and no distractions. I have most of these things now in this fallow time, with enough books to last at least another year, but my fantasy has fallen short. I am distracted, by news, by anger, by frustration, by the video calls that replace real world interaction and resonate around the small flat where we live. My job has moved from a Piccadilly office to home, and it should feel more easy to carve out extra space for reading and writing, but I have found it more difficult. Time is speeding on, with little to show for it, or so it feels. Like others, I am sleeping for longer but less effectively. In the early days of lockdown, I could only listen to books, of the comforting sort Eleanor Hardy refers to in her blog, and as a means of being lulled away from anxiety and into sleep, whereas usually I read to wake me up, to engage me, to fire me up.

Perhaps these times when we can’t read are particularly useful for thinking about reading, and to that end I’m reading What We Talk About When We Talk About Books by Leah Price, which I took out from Senate House Library before it closed. Price writes that ‘[w]hen we mourn the book, we’re really mourning the death of those in-between moments’ that makes reading possible (p. 8). Perhaps that is what we are missing in lockdown, that amorphous world without edges where work and leisure collapse into each other too easily. I was drawn to this book by the Raymond Carver reference in its title and am rewarded with clearsighted commentary that cuts through some of our romantic, imprecise notions about books and what we do with them.

This is also a good time to escape into other people’s shells through life writing. Rosamond Lehmann has always been lurking on the margins of my research on Elizabeth Bowen, but she remained distant until I found a wonderful cache of old Viragos at my local train station book swap last year which included Lehmann’s The Weather in the Streets. I have read four other of her novels since and love her vital lyricism (though I am often frustrated by her structural choices – perhaps I should try her stories instead). Patricia Laurence’s new biography on Bowen dropped through my letterbox yesterday, and it promises to uncover more about the entanglements between the two writers that will mean more after having read each.

The New Noise by Charlotte Higgins is another book swap treasure, and something I’ve been drawn to at a time as I want to think about what the BBC is and why it was founded, and how its purpose has changed. I revelled in my short time researching at the BBC Written Archives a few years ago, poking about for material on how listeners responded to hearing Bowen’s voice, the odd letter in her spidery hand, so many notes documenting thoughtful planning, benevolent bureaucracy marshalling the new magical technologies and the art they transmitted. Such a different world, yet such a short time ago. I’m hoping this book will let me stay there for a little while.

Finally, we have Ali Smith’s Winter, which I missed the first time round between reading Autumn and Spring. The final part of her quartet will be out soon. Each instalment is written at a pace, published expediently, and functions as a creative, cultural record of our time. Of course most books are that but these are especially so. I don’t read her to withdraw from the world but because her smart, thoughtful, uncompromising view of the twenty-first century is the perfect antidote to fake news, or reporting that sees balance as the inclusion of two opposing opinions without the weighing of them. They make me dare to look more bravely at the world. The magic ingredient that Smith’s work has, harder to find now than yeast or unambiguous public health messaging, is integrity.

Aimee Gasston is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the IES. She completed her PhD at Birkbeck, University of London, on objects in modernist short stories by women writers and her research interests broadly lie within the field of literary modernist aesthetics.